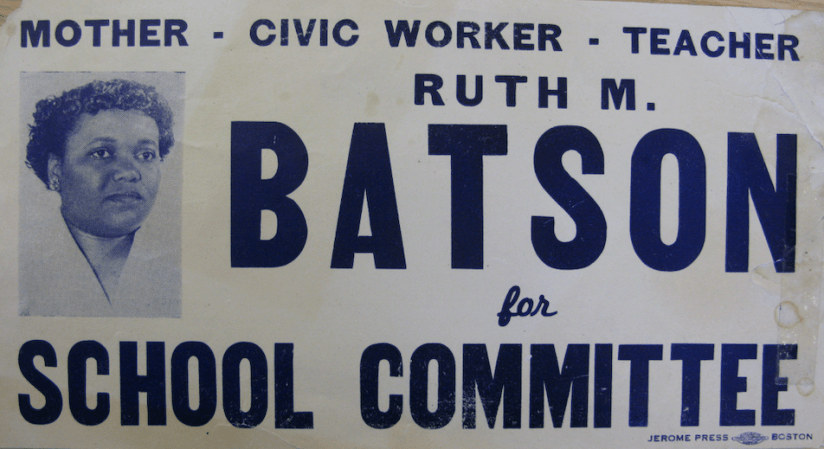

Ruth Batson was involved with METCO (Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity) a voluntary urban-suburban busing program, from its very beginning. As early as January 18, 1965, a steering committee formed to explore how to organize and establish the METCO program. At that meeting, Batson was elected to serve on the Permanent Executive Board (link). The steering committee launched METCO’s program by enlisting suburban towns to participate in the program, seeking out an executive director, applying for funding and grants, organizing busing contracts, and reaching out to the communities to create a positive interest in this new program.

“The Organizing Committee moved swiftly. Soon more concrete plans were made for the transporting of Boston students to a better educational opportunity. I had no qualms whatsoever about taking this step. I thought if I had had this opportunity for my children, faced with the open hostility that we had encountered, I would have bused my kids to California.” Ruth Batson (1)

The Organizing Committee had indeed moved swiftly; within thirteen months they had submitted a plan to the US Office of Education outlining the METCO program, had applied for funding from the Carnegie Foundation, and had four suburban communities agreeing to participate. A few months later the funding came through and two more communities had signed up. In May of 1966 the Boston School Committee voted to support the METCO program. The Organizing committee had also hired a new assistant director, Ruth M. Batson.

By the spring of 1966 Batson knew she had to act fast since seven suburban communities were ready to accept students in September. Batson reached out to Boston’s many black community organizations to explain the application process. Batson was in charge of interviewing and selecting the first students to participate in this new program, as well as speaking at informational meetings to discuss METCO and to address questions and concerns. Often she had to assure parents they was looking for a cross section of students, and not “the cream of the crop” or children of friends and family who were on METCO’s board of directors. Once the board of directors created a list of criteria for student selection the interview process could begin. The goal was to have the majority of students fall in an average range academically. They wanted all students to be at grade level, which was tricky because Batson found average grades in Boston schools translated to being academically behind compared to suburban schools. METCO staff interviewed applicants and their parents, their grades were scrutinized, and hypothetical situations were discussed. As the process continued, the suburban community interviewed students where they wished to attend school. Out of six hundred applicants, two hundred twenty students were selected to attend one of the seven suburban host schools. The following year Batson placed four hundred twenty-five students in sixteen suburban communities.

In January 1968, Batson became the Executive Director of METCO, and she served in this capacity until the spring of 1970. In this new position, Batson’s responsibilities included fund raising and grant writing; she also worked developing and maintaining relationships with superintendents of the suburban school districts. During her tenure as the executive director, METCO continued to grow, not only in number of students and suburban communities, but they also began provided a variety educational and support of services. Under Batson’s leadership, programs were established which further assisted inner-city children with educational opportunities; in conjunction with a local college, METCO organized a tutoring program for its students. They also created a job-training program “New Careers,” which worked with local businesses to train and place students in jobs and provided these students an opportunity to enroll in a basic education program or into a college. By the fall of Batson’s first year as executive director METCO’s program had doubled, with over nine hundred students attending twenty-eight suburban schools. In June 1969, Batson informed the board of directors she would be stepping down by the end of the year. The position of Executive Director was extremely demanding and she felt it was important to keep leadership fresh.

“At the end of four years with METCO, I wanted to move onto another job. An action job like METCO, in my opinion, required a change in leadership…” (2)

(pictures & documents: letters from grateful parents, pages 9-10, 14 from story of metco, link to stark & sub’s metco exhibit,

footnotes:

- Ruth M. Batson. The METCO Story. An unpublished paper written for The Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History, October 11, 1985. (The Papers of Ruth Batson, 1919-2003 inclusive, (1951-2003 bulk); The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.) Page 7

- Ruth M. Batson. Ruth Batson: Personal Statement. An interview for Boston University Community Mental Health Center Consultation and Education Program. (The Papers of Ruth Batson, 1919-2003 inclusive, (1951-2003 bulk); The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.) MC590 Box 2, folder 9

Sources:

- Ruth M. Batson. The METCO Story and unpublished paper written for The Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History, October 11, 1985 The Papers of Ruth Batson, 1919-2003 inclusive, (1951-2003 bulk). The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

- Ruth M. Batson. Ruth Batson: Personal Statement. An interview for Boston University Community Mental Health Center Consultation and Education Program. The Papers of Ruth Batson, 1919-2003 inclusive, (1951-2003 bulk). The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. MC590 Box 2, folder 9

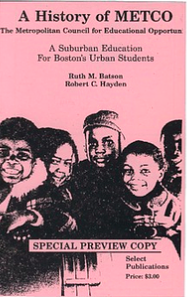

- Ruth M. Batson and Robert C. Hayden. A History of METCO: The Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity; A Suburban Education for Boston Urban Students. Boston, MA: 1986