A few years ago, I was asked if I would join the Board of Directors of a local Historical Society. I became part of a dynamic group of people, each who bring a special interest or ability to the table, and together, I think we make a pretty good team. We have a beautiful old Victorian House that is our society’s headquarters, and we are always trying to come up with novel and interesting ways to physically bring people in our doors. Those that come to visit often say, “I grew up in this town and this is the first time I have been here.” Honestly, from being an active member of a couple of other local historical societies, I know this is a refrain heard over and over again. It seems our culture values the places and people who keep history alive in town, but they rarely have anything to do with that local history. When COVID hit, we, like everyone else, had to shutter our doors to guests. Although our physical home was closed, we still wanted visitors, so we went virtual.

One member of our Board of Directors created a daily posting he called “This Day in Norwood History.” Part of our collection contains bound copies of our local newspapers, going back for several decades. Taking a cue from today’s date, he looked through our collection for interesting newspaper articles with the same date. He usually selected a short article that may have featured a business or a person or a location. He transcribed it and posted it to our home page, then linked that posting to our Facebook page….of course he included a picture to catch someone’s eye. The response was incredible! Our Facebook post was shared and shared again. People often started threads discussing their memories of topic posted, and the traffic to our home page increased tremendously! We were reaching not only local folks, but those who had moved out of town settling in far way communities.

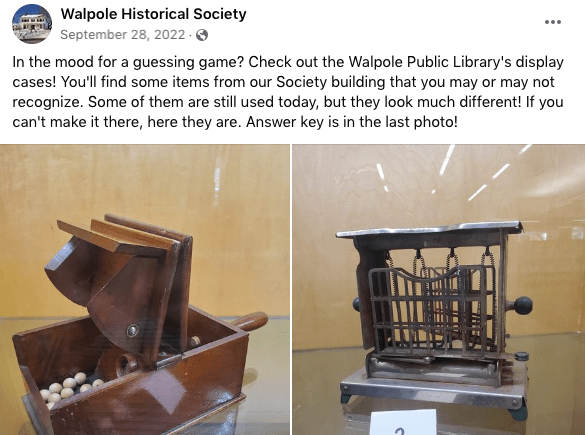

Another local historical society where I volunteer did something similar. They thought it might be fun to photograph items from their collection, and post them on their Facebook account asking people if they can identify what the item was and/or what it was used for. This was an excellent way to not only show off their collection, and to spark conversations, but an even better way to attract virtual visitors. Another take on this is posting local places long gone, and asking visitors if they know where this place was…and what is there now. Sparking a memory often will engage people, and bring you virtual visitors, who if in the area may physically walk though your doors someday.

Today, so many historical societies struggle finding ways to share a their history and trying to engage people. Using the internet effectively a small society can potentially reach millions of people. Yes, using social media like Facebook, Tik Tok and Twitter (now X), can reach a large amount of people, but your society wants to have their robust own home page. One that offers visitors online exhibits to peruse, history article to read, and a place to join or buy society swag. Using social media will catch the attention of interested people, but linking those posts to your society’s home page will bring in virtual foot traffic and educate the public on your unique history.

Initially “This Day in Norwood History,” was planned to be a program we were going to run during COVID, it has been wildly successful, and is still going today! The “What is this Item” the other historical society was doing, continues but at a more sporadically. Mostly because they are fun and engaging…which I think is exactly what history should be!