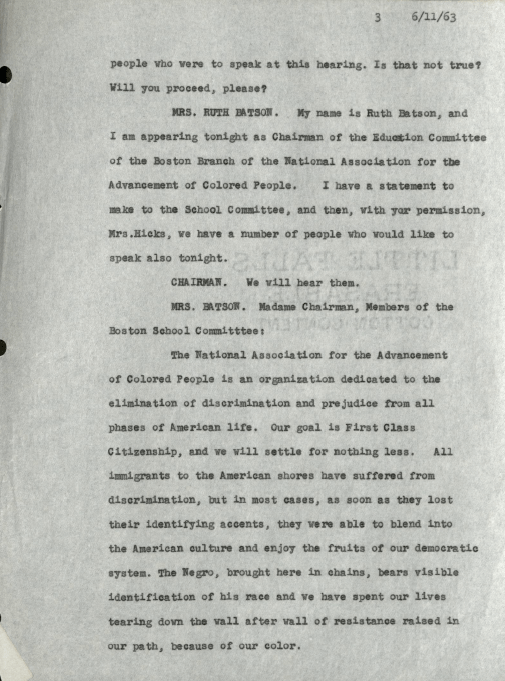

By June of 1963, The Public Education Committee of the NAACP Boston Branch was finished meeting with officials to discuss their concerns. They requested to meet (Tuesday, June 11, 1963) with the Boston School Committee so they could air a list of demands to improve Boston Schools. Ruth Batson, as chair, read a long statement her committee carefully composed specifically to call attention to their concerns. In this statement was a list of fourteen demands the group wanted addressed immediately. Minutes of this meeting show all parties involved were polite and restrained. The Boston School Committee promised to look into the NAACP’s concerns. The next day, (Wednesday, June 12, 1963) the Boston School Committee held another meeting. They questioned principals and other officials regarding the concerns and demands of the NAACP. School officials reported, for the most part, the problems were due to bad parenting, difficult students, and lack of support from the families. It was apparent to the NAACP, from the tone of this meeting and from the prior ten years of meetings with city officials, the Boston School Committee did not plan to move quickly on their concerns. It was decided by several Boston African American leaders that a peaceful protest should be organized.

The following day (Thursday, June 13, 1963) a school boycott and a march to the Public Gardens were held. The school boycott continued into the next day (Friday, June 14, 1963). On Saturday, June 15, 1963, a special meeting between the NAACP and the Boston School Committee took place at to discuss the boycott and the list of fourteen demands. The majority of the minutes from that meeting show a very long discussion regarding de facto segregation. The NAACP wanted the Boston School Committee to acknowledge that it was a real issue. The Boston School Committee did not want to acknowledge de facto segregation because they were concerned the segregation would appear to be a conscious effort by the city of Boston rather than a situation of happenstance. Eventually the school committee was willing to refer to this the situation as “residential groupings,” but little else was settled that day.

On July 15, 1963, the Public Education Committee of the NAACP Boston Branch requested yet another meeting with the Boston School Committee. They also met with the National NAACP officer to discuss the issues previously raised with the Boston School Committee. They planned out potential actions they may have to undertake in order to get the School Committee to address their concerns, including the possibility of suing the school committee. They also discussed their trepidations regarding the seven candidates to replace Frederick Gillis as superintendent. A week later, the School Committee stated that they would not meet with the NAACP. The following week, the Executive Committee of the NAACP unanimously voted to support public demonstrations. They also issued an ultimatum:

“If by Friday, August second, the school committee has not agreed to honor the request on July 15 for a continuation of negotiations between that body and the Education Committee for the NAACP, the Boston Branch NAACP with the support of every other Major civil rights organization will hold mass demonstrations at the school committee’s 15 Beacon Street offices. To begin on the next Monday, August 5th…..we are herein asking the school committee to reverse its decision of a week ago for the sake of the national image of the “All-American City;” for the sake of the neglected children of our community; and most important, for the sake of moral rectitude.” (1)

This message was sent to the Mayor of Boston and the Governor of Massachusetts. A similar message was sent to President Kennedy. Each of these politicians sent responses supporting the NAACP’s position and urging the school committee to continue discussions with concerned citizens. The school committee bowed to pressure and agreed to a meeting, but Louise Day Hicks, the school committee’s chairman, had conditions for this meeting: it could last no longer then an hour and the term “de facto segregation” could not be discussed. The meeting was held August 15, 1963, but it only lasted a few minutes. Batson read a statement and uttered the words “de facto segregation.” Louise Day Hicks banged the gavel ending the meeting. As a result, demonstrations were held throughout the month of August by organizations that supported desegregation. In September the NAACP held a sit-in at the Beacon Street offices of the Boston School Committee in hopes they would admit the problem of de facto segregation. In a statement released to the press, and published in the Sept 6, 1963 edition of the Boston Herald, the NAACP had five key issues they wanted the committee to address;

- “Open enrollment for school children

- Full consideration in locating new schools for maximum integration

- The rezoning of school districts to achieve maximum integration.

- Consultation with educational experts regarding the desegregation of the de facto schools

- A meeting with the NAACP Public School Committee to discuss further ways and means to achieve desegregation.” (2)

By September, the School Committee was once again holding meetings with the Public Education Committee of the NAACP. These meetings would continue for another ten years, as the Boston School Committee refused to acknowledge de facto segregation or that there was any unfair or unequal treatment regarding the students in Boston Public Schools. In February of 1964, Batson stepped down from her duties as the Chairman of the Public Education Committee of the NAACP because she had accepted a position at the Massachusetts Coalition Against Discrimination, but she remained on its board.

footnotes:

- Ruth M. Batson, The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events; A Chronology. (Boston, MA: Northeastern University, School of Education, 2001) pg 101

- “Mrs. Hicks ‘Tragic’ Event: NAACP Leader Blasts Committee,” The Boston Herald, September 6, 1963; page 18

Sources:

- Ruth M. Batson, “The METCO Story” and unpublished paper written for The Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History, October 11, 1985. The Papers of Ruth Batson, 1919-2003 inclusive, (1951-2003 bulk). The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Insutitute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

- Ruth M. Batson, The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events; A Chronology. Boston, MA: Northeastern University, School of Education, 2001

- Jackie Shearer (interviewer) “Eyes on the Prize II Interviews: Interview with Ruth Batson,” Washington University Digital Gateway Texts, conducted by Blackside, Inc., for Washington University Libraries, Film and Media Archive, Henry Hampton Collection, Seattle, WA. November 8, 1988

- Minutes of the Boston School Committee, June 11, 12, 15, 1963

- “Hynes to Run for Mayor Again: City Head Tips Hand in Seeking to Calm Group Irate Over Schools,” The Boston Herald Traveler, Boston, MA; December 28, 1950; page 1 and 32

- “Mrs. Hicks ‘Tragic’ Event: NAACP Leader Blasts Committee,” The Boston Herald, September 6, 1963; page 18

- George D. Strayer, A Survey of the Boston Public Schools, for The Boston Finance Committee 1944

- Cyrus Sargent, The Sargent Report, for the Superintendent of the Boston Public Schools, May 1962

- The Harvard Report on the Schools in Boston, for the Boston Redevelopment Authority, 1962

- A Progress Report, by The League of Women Voters of Boston, Education Committee, 1963