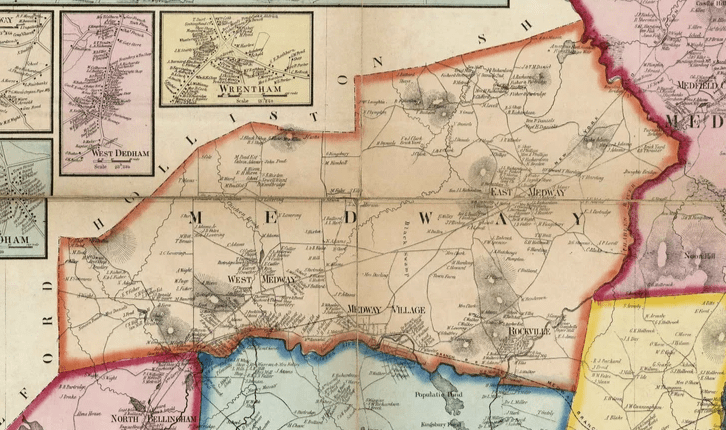

Medway was initially a part of Dedham (est. 1636), and then a part of Medfield (est. 1651), by 1712 people had begun to settle west of the Charles River, and they petitioned the Great and General Court of Massachusetts to separate from Medfield and establish their own new town. By the fall of 1713 their request was granted and the new town of Medway was established. In 1714 they built the first meetinghouse of Barre Hill. Like the other towns that were part of the original Dedham land grant, Medway was mostly an agricultural community, even though a gristmill had been established in what is now the village area a few years before the town was established. In the 1780s small businesses began to dot the area, and by the early 1800s several mill businesses were established along the Charles River; a cotton mill and a paper mill, as well as businesses that were not in need of water power; a bell foundry, cabinet maker, a straw factory that made bonnets, a boot and shoe manufactory, and a company that make church organs and pipes were just a few of the businesses that turned part of Medway into an industrial town. The town Medway encompassed a large area. In 1748, the West Medway precinct was established, essentially creating an East Medway and a West Medway, with the Black Swamp, a large undeveloped swamp in between. In 1885, East Medway precinct became the Town of Millis, and the precinct of West Medway is today the current town of Medway. It is interesting to note that the First Church of Christ of Medway is now located in Millis (today called Church of Christ, Congregational), and the Second Church of Christ in West Medway is today the Medway Community Church.

Medway has a similar history to the other original Dedham land grant towns. Records indicate people were enslaved there as early as the 1730s, but it is highly likely slavery was there years before. The records also show that slavery, as a practice, continued through the 1790s. The records from the church note the births, marriages and deaths of some “negro servants.” The 1754 Massachusetts Slave Census recorded seven enslaved people in town over the age of sixteen; four males and three females. The 1790 US Federal Census counted twenty-seven “all other people” in town. Taking into consideration the 1754 Slave census does not count free people of color or those enslaved under sixteen, then the 1790 potentially indicates that the population of people of color grew a little over twenty-five years in Medway. In 1769, the church decided to built special pews for the “Negros, Mulattos and Indians to sit in, in times of Devine service.” They were on each end of the meetinghouse, and they were to be the only place they could sit.

However, something unusual for the towns set off by Dedham appears in several newspaper articles regarding Medway, stories of aggressive behavior from enslaved or people of color in town. In 1749 the meetinghouse burned to the ground. Newspapers that reported the incident stated “tis suspected to have been set on Fire by a Negro Fellow, who had since absconded.” Other histories note that this was a rumor at the time, and that no one really knows the cause of the fire. In 1768, Newspapers reported that an enslaved man of a Mr. Turner, tried to get ratbane from a doctor, as he had plans to kill Mrs. Turner. The newspaper reports “the Negro was committed to Bridewell” and while there he unsuccessfully attempted suicide.

By 1750, Medway had grown so that a second parish was established, creating two churches in the town, The First Church in East Medway and the Second Church in West Medway. As it turns out, the ministers from both churches enslaved people. The Second Church of Christ in the West Precinct (now Medway), their first minister, Rev. David Thurston had at least two enslaved people. David Thurston (1726-1772) was son of Daniel Thurston and Deborah Pond of Wrentham. He graduated from Princeton in 1751, was called to West Medway in 1752 to be their settled minister. He married Susanna Fairbanks (int) 23 Mar 1752, together they became the parents of seven children, five growing to adulthood. In 16 Oct 1758 the birth of Cato Fortunatus was recorded in town records. They child was the son of “Fillis, negro servant of Rev. David Thurston.” Thurston asked to be dismissed of his ministerial duties in 1769, and retired from the ministry. When he left Medway he eventually settled in Sutton, Massachusetts, where he died in 1772. The administration of his estate did not include any enslaved people.

The First Church of Christ in East Medway (now Millis) was first served by Rev. David Demming (1681-1741). He arrived in 1715 and asked to be dismissed in 1722, having only been in the town for seven years. The second minister, Nathan Buckman was called in 1724 and served the community for 62 years retiring from the pulpit in 1786, but continuing with ministerial duties until his death in 1795. Nathan Buckman was born 2 Nov 1703 in Charlestown, Massachusetts, son of Joses Bucknam and Hannah Peabody. He grew up in Malden. He attended Harvard, graduating in 1721. Upon graduation he began to fill the pulpit in Medway. The parishioners immediately liked Bucknam’s preaching and offered him the position of being their settled minister. He turned them down, as he felt his age of nineteen was too young for such an important position. He accepted the job and was ordained in 1724 after he turned twenty-one. He married the daughter of Rev. Moses Fiske of Braintree, Margaret Fiske on 23 Jan 1727 in Braintree, and they became the parents of nine children.

Records of Medway show that Bucknam was one to the earliest slaveholders. There is a record of him selling his “Negro Boy,” London to Jasper Adams for £140. Bucknam had wanted a pay increase, which the church denied, so he decided to sell his enslaved boy. London’s death is recorded as 25 Feb 1792 in church records. It appears London passed to Jasper Adam’s nephew Capt. Jonathan Adams when he died in 1742. In When Nathan’s father Joses died he willed him is “negro man Pompe” in 1741. The may be the “Pomp” who’s 1785 death is recorded in town records. Bucknam also had an enslaved woman, Flora. Bucknam was paid 9s 4p for several years for having “his negro woman keeping the meetinghouse.” When he wrote his will in 1789, (six years after slavery was deemed unconstitutional in Massachusetts), he wanted “the negro woman Flora to serve her mistress (Bucknam’s wife) during her natural life.” He further added, “to my negro woman Flora, it is my will and pleasure, that if she out live her mistress that she live with one of my children, which she shall choose, if the same can take her, and that these be a suitable allowance out of my estate for her comfortable support if she live to be chargeable, or her service should not answer for her maintenance.” Flora did not live to have this “retirement.” She died 21 Feb 1792, and her master and mistress outlived her. Nathan Bucknam died 6 Feb 1795 and Margaret (Fiske) Bucknam died 1 May 1796.

Historically, one of the largest demographics in Massachusetts believed to be slaveholders were doctors, however this notion it not true in Medway. Since its establishment, Medway has been home to several doctors who set up practices within the community. It is unclear who its earliest doctors were. It is possible doctors from Mendon or Medfield had patients in Medway. The first to have an established practice in Medway was Dr. Aaron Wight, (1741/2-1813) was the son of Jonathan Wight and Sarah Plimpton of Medfield. He studied medicine from Dr. Thomas Kittridge in Andover. About the time he married Dr. Kittridge’s daughter Mary in 1767, he established his practice in Medway. The next Doctor to practice in Medway was Dr. Abijah Richardson, (1752-1822) was the son of Asa Richardson and Abigail Barber of Medway. He attended Harvard, and then served in the American Revolution as a surgeon, before setting up his practice in Medway around 1780. Both doctors began their practices at a time when slavery was still legal in Massachusetts, and died many years after it had been deemed unconstitutional, so they would not have enslaved person in their estate inventories. Also, both of their fathers were well off, and left extensive estates, but neither had an enslaved person listed in their inventories. It is highly likely that neither Dr. Wight nor Dr. Richardson were enslavers.

Medway was very much an agricultural town until around 1800 manufactories were built in the Village along the Charles River. There were only a handful of businesses in town, and it appears those who owned enslaved people were wealthy farmers who owned many acres of land and used their enslaved people as farm labor.

Jasper Adams, born 12 Mar 1674, was a bachelor farmer when he died 1 Jul 1742. His assets were divided up in to equal quarters, with each of his siblings, or their heirs, inheriting his property. In an inventory of that property was a “Negro man Servant” valued at £160, this is most likely London, the negro boy he bought from Rev. Bucknam in 1738. Jasper Adams’ nephew Capt. Jonathan Adams was the executor of the estate. It appears he ended up with London, who died in February of 1792. Although London died after 1783, when it was decided slavery was unconstitutional in Massachusetts, the notation in town records is London was the “negro man servant of Capt. Jonathan Adams.” It appears London remained with Capt. Adams, never fully taking advantage of his freedom. Perhaps he stayed with Capt. Adams as by the 1780s he would have been nearing his seventies, and it was easier to just stay put.

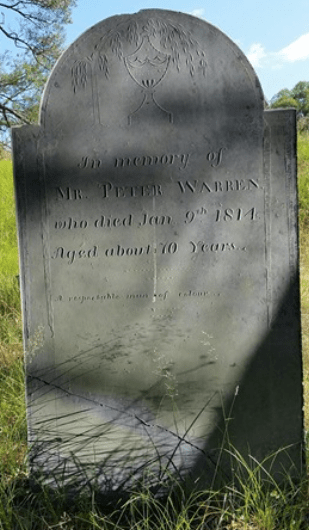

Joseph Lovell (1708-1759) was the son of Alexander Lovell and Elizabeth Dyer of Medfield. In 1739 he married Prudence Clark and together they had four children, only three grew to adulthood. Joseph was a farmer. When he died, he left half of his farm to his wife and the other half to his son Joseph, noting that Joseph would inherit his mother’s half when she died. To his daughters, he left them money. His estate was not inventoried, so the amount of real estate and personal estate it is unknown. However, in his will he mentioned his “servant,” saying: “I give my servant his freedom at thirty one years of age provided he serve my son Joseph Lovell willingly & faithfully and if not I give my son Joseph Lovell full power to sell him for his lifetime.” In 1769 Caesar Hunt alias Peter Warren, paid £13 6s 8p to Joseph Lovell (Jr.) for his freedom. In 1762, “Caesar Negro,” was paid 8s 11p for work regarding the estate of Lt. Timothy Clark. Quite possibly this is Caesar Hunt (alias Peter Warren) who was paid, illustrating that he was able to pick up paying jobs when he had some free time. In his emancipation papers, Lovell notes the receipt of the money, that Warren was a Mulatto slave having previously belonged to his father and who descended to him. He releases Warren from his service, but further notes that if Warren becomes idle and a chargeable threat to the Lovell estate, that Warren can be remanded back into “service” to the Lovell family. Warren moved to Medfield where he lived the rest of his life. There is no record of him marrying or having children, but he did serve in the militia during the Revolutionary War. Warren died in 1814, his headstone in Vine Lake Cemetery, Medfield says: “A respectable man of colour.”

Nathaniel Whiting (1691/2-1779) was the son of John Whiting and Mary Billings of Wrentham. He came to Medfield, the part that is now Medway, around 1709 when he was granted eight acres of land by the town of Medfield. Here he established a gristmill. Over the course of the 65 years, Whiting would amass real estate of approximately 618 acres of land that was in both Medway and Wrentham (the part that became Franklin). In 1711, he married Margaret Mann, the daughter of Rev. Samuel Mann of Wrentham. The couple would go on to be the parents of four children. Whiting supported the separation of Medway from Medfield, was selectman of the town for eight years (between 1723 and 1749), he served during the French and Indian War. In 1741, Whiting brought Stephen, his “negro,” to the First Church to be baptized. It is not known where Stephen came from, or even what happened to him, as this is the only record found to date, mentioning him. In 1736 Nathaniel Whiting’s father John died. In an accounting of John Whiting of Wrentham’s estate, is listed an “Indian Servant” valued at £20, who was most likely inherited by Nathaniel’s brother. When Nathaniel Whiting died in 1779, he left an estate that was valued at over £18,000. This included an enslaved man named Roger. He willed Roger to his son Nathan, but added that if Roger was to produce bonds, that would hold Whiting’s estate free from all future charges, than Nathan was to liberate Roger and set him free.

Esn. Samuel Harding was another Medfield farmer who owned a slave. Born in 1698 in Medfield (the part that is now Millis) and died in Medway (the part that is now Millis) in 1780. He was the son of Abraham Harding (1691-1734) and Sarah Merrifield. He married Mary Cutler and they became the parents of seven children. Dinah, a ”negro girl of Samuel Harding” whose birth was on 9 May 1741, was recorded in town records. In December of 1741, Harding approached the church regarding the baptism of Dinah. In the church records it says:

“Dec. 20th, 1741. Upon ye desire of Sam’l Harding and his wife to have a negro child baptized wh ye had took in its infancy for yir own. It was put to the brethren, whether, they thought masters and mistresses might offer up ye servant that they had a property in, in their minority, and they had a right to baptism upon yr account. It passed in the negative.”

Samuel and Mary Harding raised Dinah. She is mentioned in Samuel’s will as “my maid Dinah.” He notes he had given her some furniture and kitchenware in October of 1779, a few months before he died. Quite possibly this notation may indicate that Dinah was freed, but what happened to Dinah is unknown.

Lieut. John Harding was born 1694 in Medfield (the section now Millis) he was the son of Abraham Harding (1691-1734) and Mary Mason, and was the half-brother of Ens. Samuel Harding. He married Thankful Bullard, the daughter of Lt. John Bullard (1678-1754). Joh Harding was a cordwainer and one of the original signers of the petition to set off Medway from Medfield. John Harding was an enslaver to a man named Boston (1750ish-1809). How Harding acquired him and when are unknowns. His father had a large estate, but no enslaved people. His father-in-law also left a large estate and one enslaved women. So it appears he did not inherit Boston. At some point Boston was freed, and in 1780, took the name Prince Royal. Prince continued to live in Medway, he married twice, but did not father any children. When he died he left his estate to his second wife Zilpha. It should be noted, his will is 51 pages long! (these scans include the backside of every page, so his will, realistically was 25 page)

Lt. Timothy Clark (1706-1761) was the son of Timothy Clark and Sarah Metcalf of Medfield. Timothy married three times. He married first to Elizabeth Harding, sister of Ens. Samuel Harding in 1728 (one child; died young). Second to Abigail Bullard, daughter of Lt. John Bullard (three children) in 1730 and third to Margaret Whiting, daughter of Nathaniel Whiting (five children) in 1740. In 1741, he brought Charles, “his negro” to church to be baptized. This was the same day his father-in-law brought “his negro” Stephen to be baptized. In May of 1745, the town clerk records the birth of Melatia Rober, a “negro girl of Timothy Clark.” By the time Timothy Clark’s father died in 1725, he had acquired a large amount of real estate. By 1733, Timothy and his siblings could not agree on how to fairly divide up the estate, so Timothy bought out his siblings. Timothy Clark (Sr.) was described as an “Innholder” and it is said his inn was on the “Old Post Road,” and in Lt. Timothy’s inventory, his widow, Margaret receives payment for working in the tavern. When Timothy (Sr), his father died, he did not have any enslaved people listed in his inventory, but when Lt. Timothy died he had listed in his inventory a “Negro boy in his 13th year” £40 and a “Negro Girl (Melatia) in her 16th year” £30. These one of these two teenagers is nameless, and it is not known what happened to either of them.

Lt. John Bullard (1678-1754) was the son of Benjamin Bullard and Elizabeth Thorpe of Sherborn. He married 1702 to Abigail Leland, and they became the parents of seven children. Bullard received the bulk of his land from his father. It was located at Bogastow Neck and eventually divided between the towns of Medway and Holliston (now in Millis). As of 2000, his house was still standing in Millis. Bullard’s death in 1754, is the same day as Toney, his enslaved man died. John Bullard wrote a will. In it he gave his “Negro girl named Vilett” to his wife. In his inventory she is listed as “one Negro Wench, named Vilet” at £26 13s 4p. Abigail (Leland) Bullard died in 1761. She left a will and had an inventory of her estate, at that time she was no longer in possession of Violet.

William Burgess was born 1679 and died 24 Jan 1754 in Medway. It is not known where Burgess was born or who his parents were, but he was one of the founders of Medway and was there in 1712 when he married Bethiah Rocket (Rockwood). Burgess inherited much of his property from his father-in-law, Josiah Rockwood (1654-1727). The couple did not have any children. On 16 Sept 1739, Burgess brought “ye negro,” Sambo, to be baptized. When Burgess died, he left everything to his wife. No inventory was taken. When Bethiah died in 1761, she gave all her assets to her sisters and their children. Sambo was not mentioned in Bethiah’s will. It turns out Bethiah sold Sambo to John Adams of Wrentham in 1754, and in April of 1754 Sambo bought his freedom for £13 6s 8p. He settled in Holliston, married had children. He died 30 Sept 1798 at “nearly 80.”

Like its neighbors, Medway has a similar history with slavery. Those who were slaveholders were the ministers, the innkeeper, the miller and several well-to-do farmers. Records show enslaved people were here as early as the 1730s and continued to live and work in the community past the 1780s, when slavery was found not to be supported by the Massachusetts Constitution. However, Medway is unique regarding it’s history with slavery, versus it’s neighbors histories, because town documentation presents another historical aspect to consider. Church records show Medway made attempts to regulate what people of color did; they created special pews for them to use when they attended church services, and the church made decisions as to when they could or could not be baptized. Then there are newspaper reports of people of color striking out against their masters. Historians note these acts illustrate that whites and blacks struggled for some sort of power over each other. It should be noted that historians tend to study slavery larger communities, such as Boston, probably because information is easier to find. What is truly interesting to note is that this struggle for power occurred in villages like Medway and not just in large towns.