The birth of Medfield began when The Great and General Court of Massachusetts granted thirteen men the right to set off from Dedham in 1649, on the condition a village would be established within a year. This may not have been difficult to accomplish, as some Dedhamites had begun to farm the area as early as 1640, finding its expansive meadows and its proximity to the Charles River very agreeable to farming. Medfield was incorporated in January of 1651, becoming the 43rd town established in Massachusetts. Rev. John Wilson, their first minister, was soon called to minister to this growing community, which he served for over forty years. In 1655, the town voted to establish a school; Ralph Wheelock, the one of the founders of Medfield, was their first teacher. Indigenous people during King Philip’s War burned a large portion of the town in 1676, but the settlers were able to quickly rebuild what was lost. When Medfield celebrated it’s 250th anniversary, it was still largely an agricultural community, with winding waterways and lush fields. At the time of its 350th anniversary, in 2001, the town had become a commuter suburb of Boston, with the construction of several residential developments, however many open spaces continued to be undeveloped maintaining Medfield’s agricultural history.

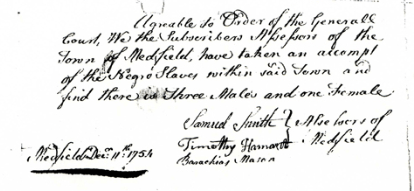

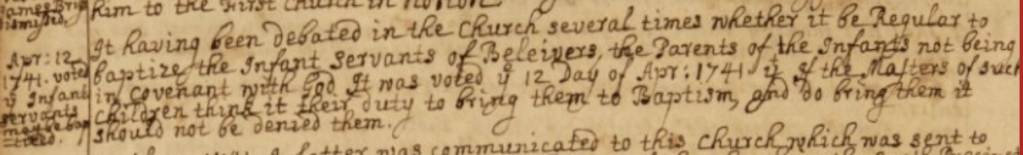

Slavery was a part of the life of Medfield, church records as early as the 1710s show several people owned slaves. In 1741, members of the church considered whether enslaved children should be baptized, even though their parents had not shared the covenant. It was decided that if their owners felt it was important for these children to be baptized, they could have the children participate in this sacrament. In the published town records, only three deaths of servants are recorded, as is the marriage of one couple. But within the church records there are recordings of servants. In 1764 and 1774, two Medfield men advertised in Boston newspapers for their run away slaves both offering a reward for their return. The 1754 Massachusetts Slave census only recorded four enslaved people in town; three males and one female over the age of sixteen. The population of people of color in Medfield, grew very little by the time the 1790 census recorded a total of fifteen “all others,” if one takes into account the possibility that there were enslaved people under the age of sixteen in town in 1754. It is interesting to note, two “all other people,” Newport Green and Warwick Green were the heads of their households in 1790. Looking for the people in Medfield who enslaved people, the known owners fall into the accepted notion of ministers, merchants and doctors, as well as farmers.

The first minister, Rev. John Wilson, who died in 1691 left a will; he does not mention any enslaved people in his will, nor are there any servants recorded in the inventory of his estate. The third minister, Rev. Jonathan Townsend (Jr), did not personally own slaves, but his father, the minister of the Needham church was a slave owner. It appears the fourth Minister, Rev. Thomas Prentiss, may not have owned slaves. He did not baptize (or at least record the baptisms of) any enslaved people during his time serving in Medfield, and he died many years after slavery had ended in Massachusetts, so none would be found or listed in his estate.

However, the second minister, Rev. Joseph Baxter was indeed a slave owner. He was born in Braintree in 1676, the son of Lieut. John Baxter. He graduated from Harvard in 1693 at the age of 17. He filled the pulpit in Medfield, before he was officially called to be their minister in 1696. He married three times; first about 1700 to Mary Fiske (the daughter of Rev. Moses Fiske of Braintree), then to Rebecca (Lee) Saffin in 1712, and thirdly to Mercy (Stoddard) Brigham in 1715. Medfield town records show that Mary Fisk was the mother of his seven children.

In 1717 Rev. Baxter was asked by the governor of Massachusetts, Samuel Shute, “to disseminate the Gospel among the aborigines of the East,” meaning Maine, which was a district of Massachusetts until 1820. Baxter first traveled to Maine in August of 1717 returning in May of 1718. He went back to Maine in August of 1721, but only stayed a little over a month coming back to Boston in September of 1721. In his journal he notes being in mostly in coastal towns of what today is Sagadahoc County; Arrowsic, and Georgetown and Brunswick. His journal also discusses meetings he had with the Abnakis as well a preaching the Gospel to them.

Baxter had a slave as early at 1714, when town records, note Tony, his enslaved man was paid to ring the bell of the church. Tony’s death is record in church records on November 7, 1757. When he wrote his will on 21 Feb 1743/44, he left to his wife Mercy “the service of my negro slave, Nanny, during my wife’s life. And to my said negro slave, I give her freedom at my wife’s decease.” But three months later, on May 2, 1744, he wrote a codicil to his will regarding Nanny. In this codicil he states that Nanny may be given her freedom if she carries & behave herself dutifully, then at his wife’s death she may be freed. He also notes his wife has full power to sell Nanny if she chooses. Nanny or Anna was baptized September 12, 1736, which is also the same day she owned the covenant. Rev. Joseph Baxter died May 2, 1745 in Medfield in the 48th year of his ministry. Mercy (Stoddard) Baxter died in 1769. It is not known what happened to Nanny after the death of Mercy. She would have been an adult at the time she owned the covenant in 1736, placing her time of birth somewhere in the 1710s. She most likely was in her 50s when Mercy died, certainly young enough to live for many more years, but town records do not record a marriage or death for her nor do they show her appearing on the town’s poor rolls.

The first doctor in Medfield was Rev. John Wilson. He graduated in the first class at Harvard in 1642. He apparently was not only educated in Theology, but Medicine as well. Records indicate he was not a slave owner. The Second Doctor in Medfield was Dr. Joseph Baxter (Jr.), son of the second minister. He attended Harvard, graduating in 1724, he returned to Medfield to practice medicine. He died in 1732 from small pox. It does not appear he ever married, or owned a slave, but he did grow up in a home with enslaved people, as his father was a slave owner.

The third doctor in practice in Medfield was Dr. Jacques “James” Jerauld. He was born 1686 in France, arrived in Boston around 1705 and was in Medfield by 1718. He married Martha Dupee/Dupuis about 1710, they became the parents of nine children. In 1721 Jerauld bought Joseph Adams’ property on the Dedham Road in the easterly part of Medfield. It is said he “had a large landed estate there which he cultivated with slave labor.” On July 16, 1738 the church records that, Ellen – “Doctor Jero’s negro woman,” and Deliverance — Doctor Jero’s negro girl” were baptized. On March 30, 1740, “Bethuel son of Doct’r Jero’s negro woman, was baptized” and on July 11, 1742, “Nathan, the son of Ellen Dr Girauld’s negro woman was baptized,” and Ellen, was received in full communion on 19 Dec 1744. It appears that Deliverance, Bethuel and Nathan were all Ellen’s children. Doctor Jerauld died in 1760. In his will he wanted “all my negros to be at her (his wife’s) disposal forever.” However, he further adds “only I will that my negro Cesar be not sold or disposed of by her (his wife) out of my family. That is to say be sold to any excepting to som (sic) of my children and theirs during his life.” In the inventory of his estate, he had one negro man, presumably Cesar who was valued at £17-6-8, one mulatto woman (£13-6-8) and one negro woman (£13-6-8). It is highly likely the “one negro woman” is Ellen, if she had been with the family for over thirty years, the family may have been fond of her, which would be why Dr. Jerauld did not what her to leave the family. Martha (Dupee) Jerauld, died three years after he husband in 1763. Martha left a will giving her “male & female negros,” as well as her entire estate to her daughters Hannah and Susanna, less cash legacies to her sons. The estate did not have an inventory noting how many male and female enslaved people Mrs. Jerauld owned. Susanna died in 1770 and it appears her share of the estate became entirely Hannah’s. Hannah died in 1786 leaving her estate to her “cousin Ruth Salmon.” An inventory of the estate was done and it appears, over the years, Hannah and Susanna had gotten rid of most of it, but most importantly no enslaved person is mentioned in her will. If Hannah and Susanna’s father laid out in his will that his female slaves were not to leave the family, then perhaps Ellen was given her freedom or she took it sometime after the Judge Cushing declared slavery went against the Massachusetts Constitution. But it is actually unknown what happened to Ellen.

From studying mostly the records of the church, there were quite a lot of enslaved people who lived and worked in Medfield. The church records are a better source of this information, as the published vital records of Medfield, only included one marriage and three deaths of enslaved people in the publication. By identifying Medfield owners of some of the enslaved, as found in church records, and then researching them, may help to discover who they were and why they came to own enslaved people, and may help to illustrate the lives of those they enslaved. From researching the owners of Medfield’s enslaved people shows that there were several merchants among these owners; a couple of Innkeepers, a Potash works owner, and a miller. However, most often Medfield slaveholders appear to be farmers, not subsistence farmers, but ones who appear to own an extensive amount of property. Some of these owners include:

Hon. Joshua Morse, inn holder, gristmill/sawmill operator. Had a large property. He served the town in many capacities, even representing them in the General Court. He was born 2 Apr 1677 in Medfield and died 26 Apr 1749, he was the son of Samuel Morse and Elizabeth [?]. His grandmother, Hannah (Phillips) Morse married a second time to Thomas Boyden, father of Capt. Jonathan Boyden. Joshua married (1) Elizabeth Penniman (1679-1705) and (2) Mary Paine (1680-1746). He was the father of eleven children – Appears to be the Joshua Morse who owned Dinah who bapt/owned the covenant in 1742. Joshua left a will, no mention of any enslaved people, nor is there an inventory of his estate.

The Boyden Family. Church records record the deaths of three enslaved men owned by Boydens. One of the earliest records is the death of Kuce in 1718, an enslaved “indian servant” of Capt. Boyden. Thomas Boyden’s “negro servant,” John died in 1746 and Dea. James Boyden’s “negro servant,” Violet died in 1780. Jonathan, Thomas and James Boyden are difficult to identify in records, mostly because Thomas moved to Wrentham shortly after he married, and his son, James grew up there and lived there his whole life. It appears “Capt. Boyden” is Jonathan Boyden, born 20 Feb 1652 in Boston and died 30 May 1732 in Medfield. It is his line that settled in Medfield. He was very involved with local affairs, serving as a selectman of the town for four years, his name appears on a committee that protested the division of the town in 1712 to set off Medway, and he was Captain of the militia also in 1712. Thomas (1681-1771), his son, is the only Thomas who was alive in the 1740s and in the area to be the Thomas who’s negro servant, John was baptized in 1741 and died in 1746 in the Medfield church. Boyden genealogies and town records show Thomas lived in Wrentham, however, at that time, today’s town of Norfolk, which abuts Medfield at its southern border, was still part of Wrentham. The trip to Wrentham village from Norfolk to attended church is a 6½ mile trip, where to attend church in Medfield was a 3 mile trip. It is highly likely Dea. James Boyden (1709-1779) is Thomas’s son. In Wrentham vital records, it records the death of James and Hannah’s daughter, Abigail in 1757. It records the death of Dea. James and Hannah’s daughter Abial in 1776. According to Medfield church records, James was made Deacon in 1760. So James, son of Thomas, who lived in Wrentham, appears to be the James who was a Deacon of the Medfield church. These three Boydens appear to be the correct Capt. Boyden, Thomas Boyden and Dea. James Boyden in Medfield church records. There is not a record (will/administration) of Capt. Jonathan Boyden’s estate. Thomas left a will, but does itemize his possessions, nor is there an inventory of estate on file. So it is unknown if Jonathan and Thomas owned any enslaved people at the time of their deaths. However, Dea. James left a will. He gave “Lettie” to his wife. She appears to be the Violet who died in 1780. He also had two other enslaved people, Rueben and Pegg. He also states if they “behave disorderly,” they are to be sold and the money from the sale is to be equally divided between his wife and eleven children. He further states if they “behave orderly,” then Pegg is to go to his wife and Rueben to his son Jarius. It does not appear that any of these Boyden’s were business owners, but simply farmers, however it does appear they owned an extensive amount of land, and perhaps they needed slave labor to help maintain it.

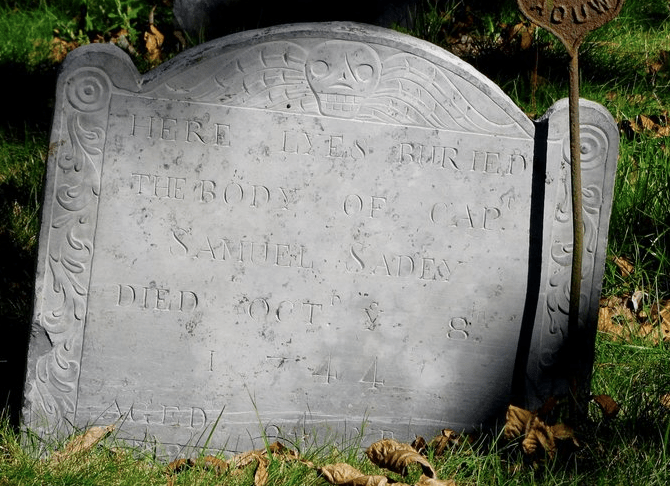

Capt. Samuel Sadey, was an inn holder on North Street. He was born 6 Feb 1681 in Boston to John Sawdey & Elizabeth Peters. He married 25 Sept 1707 Mary (Johnson) Hernden in Andover, MA. (She was originally from Medfield). He appears in the muster rolls of Capt. Eleazer Wheelock, serving as a Cornit. He served from Oct 11, 1723 to Oct 31, 1723. In 1734, his name is on a list of proprietors in Keene, NH, but he was back in Medfield by 1735 when his “negro woman servant,” Keturah was baptized. Keturah’s death is also recorded in church records on 15 Mar 1742/3. Capt. Sadey died Oct 8, 1744 in Medfield. Mary his wife was the executor of his estate, in the inventory he lists a “negro maid.” Mary his wife died Dec 18, 1763.

Nathaniel Smith, was born in Medfield Oct. 31, 1684, the son of Samuel Smith and Sarah Clark. He married (1) May 24, 1705 to Mary Clark in Medfield. She died 1717. Nathaniel married (2) abt. 1719 to Lydia Partridge. He had a large property on South St. He sold out to his son Elisha in 1755 and moved to Sturbridge where his sons, Joseph and Nathaniel lived. Nathaniel Smith died in 1762. It is unclear why he would have enslaved people, yet he had Jane, negro child under his care baptized 19 Jul 1741. The child’s death is recorded in church records on 27 Mar 1745.

John Greene, came to Medfield around 1770 coming from Boston. Greene was born in Boston 24 Dec 1731 and was the son of Thomas Greene and Elizabeth Gardiner. He married in 1757 to Catherine Carr in Newport, RI. The couple did not have any children. Their portraits, done by Copley, are part of the collection in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Greene bought the house at 505 Main Street from the estate of William Plimpton. He was a very successful merchant. He operated Medfield’s Potash works. Not only did Greene come with his wife, Catherine, he also brought with him his enslaved people, which included Warwick and Grace. In 1776, when Greene was drafted by to serve in the militia, instead of going himself, he sent Warwick to serve in his stead. If an enslaved person served in the Militia, they would receive their freedom. John Greene died 29 Nov 1781 in Medfield. (online sources say he died 2 Dec 1781 in Boston, this could be from probate documents.) Greene had a will in which he gave “my negros” to his wife. An inventory of the estate does not count (or name) his “negros.” His will mentions his siblings: Nathaniel, Thomas (deceased), Joseph, David and Mary Hubbard (wife of Daniel Hubbard).

Another source in information regarding Medfield slaveholders are Newspapers. Two advertisements, one in 1764 and the other in 1774, in Boston Newspapers regarding the run away “Indians servants” of two Medfield men, actually leads to an interesting history. The 1774 advertisement is not as interesting as the 1764 advertisement, but it bears mentioning. On November 10, 1774, in the Massachusetts Spy, Elijah Allen of Medfield ran a notice for his run away “Indian Boy,” Benjamin Thomas. He provides the age and description of the boy and offers up a reward of a Half Dollar for his return. The out come of this situation is unknown. However, the outcome of an advertisement published ten years earlier in the Boston Evening-Post, where Seth Dwight of Medfield was looking for the return of his “Indian Man Servant,” Ebenezer Ephraims, on October 22, 1764. Dwight gave a physical description of Ephraims, and included his age and what he was wearing. Dwight offers a reward of One Dollar plus expenses for Ephraims’ return. This ad ran several times in October and November on 1764. It appears Ephraims never came back to Medfield.

Ebenezer Ephraim was baptized 26 Jul 1747 in Natick, the son of Peter Ephraim and Hannah Weebucks (this couple appears to be free). Peter died in 1753 and Hannah in 1759, orphaning three children under ten and two teenagers. Peter’s estate was valued at £394 and was divided up amongst his heirs. It is possible Ebenezer came to Medfield soon after the deaths of his parents, perhaps as an indentured servant, under the custody of Seth Dwight. After Dwight’s 1764 advertisement, Ebenezer next appears in records in August of 1767 in Medford, Massachusetts (warning out) where he secured a room in the home of Gideon Gardner. In 1775, Ebenezer Ephraim was living in the Worcester area, where he enlisted to serve an eight-month term in the Militia, where he was one of fifteen Indigenous Men who fought at Bunker Hill. He died just before he was to start his military service in January 1777.

Medfield’s vital records and histories show that the town has a long history of enslaved people living and working in its community, lasting from 1714 (and possibly before this date) and running up until (and possibly through) 1783 when Judge Cushing decided that slavery was deemed unconstitutional in Massachusetts. The known records of Medfield’s enslaved people are most likely a reflection of those enslaved people who lived here. It is highly likely many more enslaved people lived in Medfield but lives were not recorded in any record.

It is interesting to note, that when Tilton published History of the Town of Medfield, Massachusetts: 1650-1886, in 1887, and in 1902 booklet Medfield Massachusetts: Proceedings at the Celebration of the Two-Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Incorporation of the Town, June 6, 1901, do not mention the history of slavery in the town. The book Vital Records of Medfield, Massachusetts to the End of the Year 1849 also published in 1902 lists the three deaths and one marriage of enslaved people. It appears that either slavery in Medfield was a topic people did not want to discuss, or it was a topic many knew too little about to discuss.

In the mid-1800s, Medfield had a robust Abolitionist movement, and the even sent their sons to fight in the Civil War; but most interestingly, Medfield is a known stop on the Underground Railroad. Medfield was on the Fall River Line. Escaped slaves arrived by boat in Fall River, traveled to Norton, through the Attleboros, and then on to Medfield, where Rev. Luther Lee, Joseph A. Allen and his father Ellis Allen were operators. The Allen home was located at 260 North Street. It was here the fugitives were given lodging, food and clothing. After the Medfield stop fugitives continued to travel north.