Dedham when it was initially settled was a patchwork of forest, meadow and swampy land. But by the end of the 1600s, Dedham was a well-established village, with not just local tradesman and farmers living within its borders, but also living there were a few wealthy Boston estate owners, some who owned enslaved people. In 1681 an accounting was taken of enslaved people living in Dedham. There were 112 homes in Dedham, which no longer included Natick, Medfield or Wrentham lands, and twenty-two of these homes had twenty-eight enslaved people living in them. Most of these servants were white, but there were two “Negro boys,” two “Indian boys,” and one “Negro man.” In 1691, when Dr. Jonathan Avery died he had one “Negro Maide” in his inventory. Some sixty years later, in 1754 Dedham recorded seventeen enslaved people over sixteen in the Massachusetts Slave census (twenty-one if Needham (1), Walpole (1) and Bellingham (2) are included as they were part of 1681 census), and twenty-five years after that, in 1790, in the US Federal Census, they recorded sixteen “all other people” (thirty-four if Needham, Bellingham and Walpole are included). These censuses, illustrate that not a lot of enslaved people lived in Dedham, but the number of enslaved people who lived and worked in Dedham remained relatively unchanged for around one hundred years.

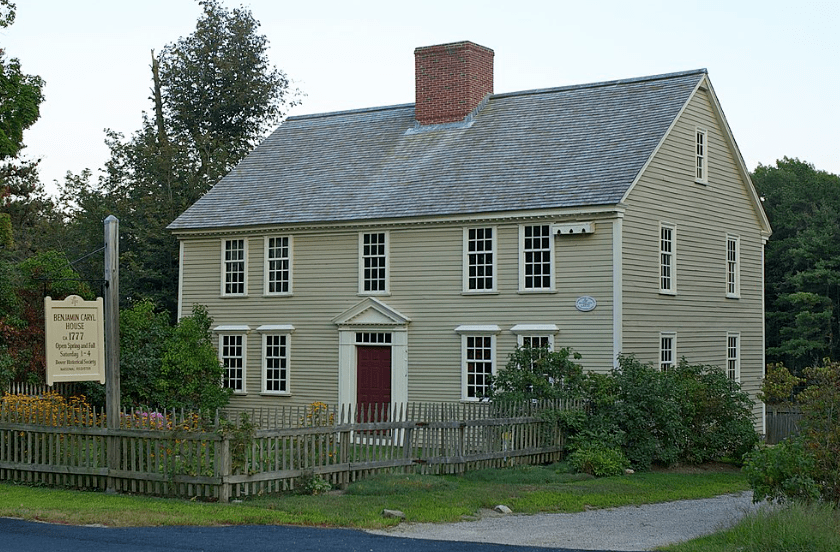

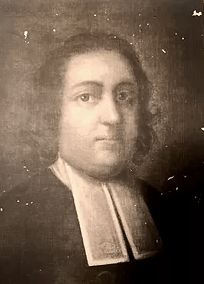

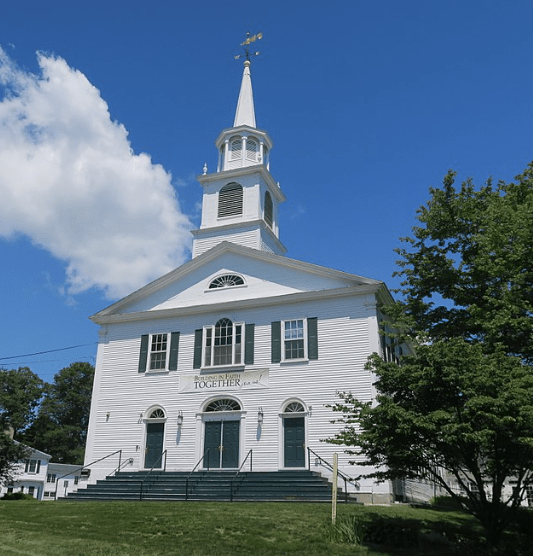

In 1754, when the Massachusetts Slave Census was taken, Dedham had four Parishes, these parishes would eventually become, Dedham (proper), Dover, Norwood and Westwood. This means there were four ministers in town, and in three of the Dedham parishes, it can be confirmed that their ministers were slaveholders. The only Parish where this is unclear is in the Fourth Parish (now Dover), as published records do not show one way or the other if their first minister, Rev. Benjamin Caryl (1732-1811) owned slaves. Caryl was called to the church in 1762, a time when many ministers were slave owners. Dover’s published records did not record any “Negros” in their vital record book, and Caryl died after slavery was deemed incompatible to the Massachusetts Constitution, so an enslaved person would not have been recorded in his estate. In Dedham Village (the first Parish), Rev. Samuel Dexter (1700-1755), was the fourth minister to serve the community. In church records he recorded that on 28 Feb 1741/2 “Primus, my negro servant” owned the covenant and then in 1752, he records the marriage of Primus, “negro servant of Rev. Sam’l Dexter to Violet, negro servant of Capt. Aspinwall of Brooklyn (Brookline).” When Dexter died in 1755, an inventory of his estate did not include any enslaved people. It should be noted that published church records do not indicate Rev. John Allin, Rev. William Adams or Rev. Joseph Belcher had any “negro servants” and a check of their wills/administrations and estate inventories confirm this. Over in the Third Parish (now Westwood) the second minister, Rev. Andrew Tyler (1716-1778), who married the granddaughter of Rev. Joseph Belcher, noted in church records payments for his “Negro servant, Weston” to sweep the church in from 1748 to 1756. When he died in 1778, he did not have an enslaved person noted in his inventory, nor did first minister, Rev. Josiah Wight.

In the Second Parish (now Norwood), their first minister, Rev. Thomas Balch (1711-1774) owned a woman named Flora. In church records, he recorded she gave birth to a stillborn child in March of 1743. Then, in August he recorded Flora’s death on the 14th and the death of her infant son Peter the day before. It appears Peter and the stillborn child were twins. Flora was young, as Balch recorded her age as “about 18 years.” Where Flora came from or if Balch bought another enslaved person is unknown. He did not have one noted in his 1774 will or estate inventory. He did not inherit Flora from his father, as he did not have an enslaved person listed in his will or inventory. Nor did she come from his father-in-law, Edward Sumner of Roxbury because when he died he did not have any enslaved people listed in his estate. However, what become apparent, is Sumner’s children were very successful and gained considerable wealth and that brought with it slave ownership.

The Sumner family of South Dedham actually originally came from Roxbury. Ebenezer Sumner (1676-1763), married Elizabeth Clap and together they raised ten children. One son, Ebenezer (1722-1745) died shortly after he returned from Cape Breton, his death is mentioned in South Dedham Church records. Three of their children settled in the Second Parish of Dedham; daughters Mary (Sumner) Balch (1717-1798), Hannah (Sumner) Newman Metcalf (1715-1796) and Deacon Nathaniel Sumner (1720-1802), all of who enslaved people. As already discussed, Mary (Sumner) Balch, and her husband Rev. Thomas Balch had enslaved people. The death of Eunice, “the baptized Negro of N. Sumner” Mary’s brother, Deacon Nathaniel Sumner is recorded in church records in 1774. In 1781, Nathaniel Sumner signed a certificate stating he hired Francis Cooler, a servant of Shubael Downs of Walpole to serve for him in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. Mary’s sister, Hannah, married twice; First to Rev. John Newman (1716-1763), who ministered in Edgartown, Massachusetts. He died young. He would have had a considerable estate, but there does not appear to be an administration or inventory on file. Besides ministering to the people of Martha’s Vineyard, he also formed a successful business partnership with his brother-in-law, John Sumner, who enslaved people. Hannah returned to South Dedham where she married secondly, Jonathan Metcalf, Esq (1715-1788). Metcalf paid £66 for a Cuff Sprague, Dr. Joseph Sprague’s “negro servant” to serve in his place in the Revolutionary War. Metcalf recorded 3 “servants for life” in the 1771 tax valuation. Metcalf died in 1788, after slavery was deemed unconstitutional in Massachusetts, so he technically could not have left enslaved people in his will/estate inventory. It should be noted, that in the 1790 US Federal Census, Widow Metcalf has 4 “all other people” living in her home. It is highly likely these “all other” people are the enslaved people her husband recorded in 1771.

The fourth parish of Dedham (today’s Dover), was established in 1747 and was called “Springfield Parish.” People began settling in this furthest part of Dedham by the 1670s, and by 1725 residents of the area petitioned the state to be free from paying the minister rate. Their request was granted, but they needed to attend church in Medfield or in Natick. One of the earliest settlers to the area was Thomas Battle/Battelle in 1671. The Battle family lived here for generations and were involved in the community. Thomas Battle’s grandsons John, Jonathan and Nathaniel were among the signatories petitioners to establish the parish. Nathaniel Battle was born in 1701, son of Jonathan Battle and Mary Onion, and Nathaniel was an enslaver, having a “servant for life” listed in the 1771 Massachusetts Tax Valuation. In 1727 he married (1) Tabitha Morse and together they had nine children. Because they lived close to the Natick border, the baptisms for their children are recorded in Natick church records. Tabitha died in 1764, and Nathaniel married (2) Silence Kingsbury (no issue). When Nathaniel died in 1778, his estate was administered. The inventory of his estate does not include an enslaved person. It appears he either sold the “servant for life,” or he/she died. It is interesting to note that in the will papers Silence Battle and her step-son Nathaniel (Jr.), who was the first person to attend Harvard in town, disputed ownership of a parcel of land. Nathaniel (Sr.) Battle’s nephew Jonathan (1724-1758), was the son of Jonathan Battle and Elizabeth Barber. He married in 1754 Love Whitney, and together they had one son. Jonathan died in 1758. He left a will, which says it is “My will is that my wife have a negro boy, which I have of about three years and seven months old…” It is clear the Battle family owned a lot of land in Dover and Natick, but it is unclear what they did for a living….perhaps just farming. Early tavern owners in Dover were Ebenezer Newell (1712-1796), who bought the Daniel Boyden farm on Strawberry Hill in 1749. He was a cooper, a farmer and a tavern keeper. He sold his Dover property in 1769 to Daniel Whiting (1732-1807) his home was located on Dedham Street. He was very involved with the Continental Army and just before the war he sold his lands in Dover. It seems John Reed (1741-18??) owned the tavern for approximately twenty years during the war and until about 1799. John Williams (1774-1840) was the next owner of the tavern. The Williams Tavern, was a stop were travelers could take a break from a bumpy ride and coachman could change out their horses, but for a as it came to be known was a meeting place and a post office. The building burned in 1908. It is highly likely that several of the owners of the tavern enslaved people, but all died after slavery was deemed incompatible to the Massachusetts state constitution.

Over in the third parish, the Richards family of the Clapboardtrees, now Westwood, was another family who owned slaves for several generations. John Richards (Sr.) (1673-1719), was the only son of John Richards and Mary Colburn. His grandfather, Edward Richards was one or the original settlers of Dedham, where he acquired large tracts of land. Although the bulk of Edward’s estate passed to his second son Nathaniel, instead of to his first son John, the latter still managed to leave behind a generous estate to his wife and children. John married Judith Fuller (1673-1744), she was the daughter of John Fuller and Judith Gay. They had four sons, identified in John’s 1719 will: John (1698-1773), Joseph (1701-1761), Timothy (1705-1788), and Samuel (1711-1764). John died in January 1719, in his will he leaves his “negro woman named Janne and his negro boy named Dik (Dick?) to be at her (Judith’s) disposal.” In November of the very same year, Jane married Diek, servant of William Briggs of Boston. In February 1741/2 Mrs. (Judith) Richards’ “negro servant,” Charles owned the covenant. This appears to be the same Charles that Judith’s son Samuel freed in his 1764 will. Judith did not have a will. Three of their four sons can be identified as enslavers.

John Richards, Jr. (1698-1773) was the eldest son of John Richards (Sr) and Judith Fuller. John (Jr) inherited about 100 acres from his father in the Clapboarded trees (now Westwood). He married in 1722 to Abigail Avery, daughter of Robert Avery. Together, this couple became the parents of seven sons. In his will, John (Jr) left his “Negro boy, Felix,” to his sons John and Abel. It should be noted in in the 1790 US Federal Census, Abel has one “all others” living in his home. Perhaps that is Felix. His brother, Dr. Joseph Richards (1701-1761), graduated Harvard in 1721. For a while he practiced medicine. He married first in 1726 to Mary Belcher (1701-1746), daughter of Rev. Joseph Belcher and he married again in 1748 to (2) Elizabeth Dudley. He was the father of ten children. In 1740, his servants Benjamin and Hager married. In the inventory of his estate did not list any enslaved people. Youngest son, Samuel Richards (1711-1764) married Rebecca Fisher (1712-1740), daughter of Joshua Fisher. Samuel and Rebecca became the parents of four children who all died young. When Samuel died he did not have any direct heirs, so he left his estate to his nephew, Edward (son of John, Jr). He gave to his “Negro Servants, Charles & Cyrus their freedom forever.” It appears that after his wife and children died, he lived with his mother, as the marriage of “Primus, servant man to Maj. Fenno of Milton & Jenne, servant woman to Sam’l & Judith Richards of Dedham,” is recorded on 1 Jan 1749/50.

The Fisher Family: Esther Fisher’s (1682-1773) name only appears a couple of times in Dedham records. She lived in the Clapboardtrees district. She was born 27 Feb 1682, daughter of Joshua Fisher and Esther Wiswall. In Nov of 1703, she married Daniel Fisher (1682-1758). Daniel Fisher was an extremely wealthy man, having real estate in Dedham, Stoughton and Walpole. When he died, his estate was valued at £2,709 and included a negro servant woman and a negro servant boy. On April 22, 1761, Rev. Andrew Tyler of the Third Parish Church, married Rozilla Adam, “negro servant to Esther Fisher,” to Sharper Goulden, “Negro servant to Capt. James Draper.” James Draper (1691-1768), lived in the Green Lodge area of Dedham where he was a farmer and had a fulling mill. He served in the French and Indian War, and was captain of the “Trained Bands.” When he died in 1768 and inventory of his estate did not record any enslaved people. Esther Fisher married secondly December 14, 1761 by Rev. Tyler to John Helyer (1714-17??) of Boston. In November of 1773, Ebenezer Fisher, the administrator of Esther Helyer estate, advertised in local Dedham newspapers for debtors to settle up with the estate, and he also advertised…

“To be sold, belonging to the Estate, Four likely Negro Children, viz. A Boy of ten Years, another of Four, A Girl of seven, another of about two Years old.”

As per the Bodies of Liberty, children born to enslaved women are the property of the enslaved woman’s master. It appears Sharper and Rozilla had four children between 1763 and 1771. What happened to Sharper and Rozilla or their children is unknown.

These branches of the Fisher and Richard and Sumner families confirm that slavery occurred in Springfield Parish, in South Dedham and in the Clapboardtrees. However, Dedham Village was more established, having small businesses and large farms, the need for enslaved labor was more demand, and therefore more prevalent. From studying information found in the First Church records, then researching the families who were enslavers by studying their estates, it starts to become clear that the majority of Dedham Village slaveholders participated in slavery for several generations, and that they were all related.

Joshua Fisher (1675-1730) was the son of Joshua Fisher and Esther Wiswell. He inherited a large estate from his father, which included the Fisher Tavern, but no enslaved people. Fisher, like his father and grandfather before him, was very involved in town affairs. He was the town representative in the General Court for two years in 1725 and 1726. He was known as “Lieutenant Joshua Fisher,” indicating he had some sort of military experience. Around 1695, he married Hannah Fuller, she was the daughter of John Fuller and Judith Gay, and the sister of Judith (Fuller) Richards. Together Joshua and Hannah had five daughters, four growing to adulthood. Joshua Fisher died 11 Mar 1730 and left a will and inventory, which included a “Negro Slave £80.” He left his entire estate to his wife, noting what parcels of land and money each daughter would receive when their mother died. When his wife Hannah (Fuller) Fisher (1675-1744), died she too had a will and an inventory that included “one Negro woman £80.” By 1744, two of Joshua and Hannah’s daughters had died. Daughters Hannah (1700-1771) and Judith (1704-bef 1771) and their husbands, along with Samuel Richards, the widower of Rebecca (1710-1734) and father of their three children, felt that their sister, Mary’s (1707-1737) share should be divided up to the surviving Fisher heirs. However, Mary’s widower, Nathaniel Ames, felt he should inherit Mary’s share, which included the Fisher Tavern. It should further be noted that Nathaniel Ames and Mary Fisher had a son, who died in infancy; Ames noted he was both Mary and their infant son’s heir. By July 1745 this family fight turned physical, as Benjamin Gay (Hannah’s husband), John Simpson (Judith’s husband) and Samuel Richards (Rebecca’s widower) attacked (or was attacked by) Nathaniel Ames (Mary’s widower). The Fisher brother-in-laws claimed Ames had stolen hay from THEIR field, and Ames said it was HIS field that he inherited from his wife’s estate. Also caught in this altercation was “one Catoe a Negroe of said Ames,” who was assaulted. The family took their case to court, Ames v Gay et. al. was first heard in October 1746, in which the court found for Gay. Ames appealed in 1748 and again in 1749, when the court reversed its original decision and found for Ames.

Dr. Nathaniel Ames (1708-1764) was born in Braintree, son of Nathaniel Ames and Susanna Hayward. He graduated from Harvard and settled in Dedham in 1732. He published an annual almanac for over thirty years, practiced both law and medicine, and ran the Fisher tavern which he renamed the Ames Tavern. Nathaniel married again, Deborah Fisher, a cousin of his first wife, and together they became the parents of six children; one son, Nathaniel becoming an important actor in town affairs and the other son, Fisher becoming a US Senator. He died 11 Jul 1764 and left a large estate including three enslaved people: “A Negro man named Cato £33 6s 8p,” another “named Jack £40,” and “A Negro girl named Jenny £33 6s 8p.” Cato had been with Ames for many years. In 1741 he ran away from Ames, heading for Cape Breton. Ames took out an advertisement offering a reward for for his return. At that time, Cato was 21 years old, making his birth year around 1720. Ames’ wife Deborah continued to run the tavern until her death in 1817. In the 1771 tax valuation she is recorded as “Wid. Deborah Ames” and she had 2 “servants for life.” The name was changed to the Woodward Tavern when Deborah married secondly to Richard Woodward. He was the widower of Susannah Luce, the daughter of Peter Luce. This marriage did not last for long as Richard and Deborah divorced and Richard moved to Connecticut.

Eliphalet Pond (1704-1795) was born 1704 in Dedham, son of Jabez Pond and Mary Gay. In 1728 he married Elizabeth Ellis, and together they had ten children, six that grew to adulthood. Pond appears to live in Dedham, although his father owned land on Strawberry Hill (in today’s Dover), and some of his siblings married into Medfield families. In some documents Pond is listed as “farmer,” “gentleman,” and “Esq,” which illustrates a rise in social standing, but not indicating how he earned his living. However, we know, Pond owned a 200 acre farm in the part of Dedham called “South Plain,” today the land that was Pond’s farm is located on Washington Street (Rte 1A) and Chickering Road on the Westwood line, which would help to understand his need for an enslaved worker. Pond was very active in his community, he served as town clerk for twelve years, was a justice of the peace, was a selectman and represented Dedham in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. In 1771, Pond shows he has a “servant for life,” in the Massachusetts tax valuation. It is unclear who this servant was, however, an incident that occurred in early September 1774, gives us a clue as to the identity of this “servant” – apparently, an angry mob of Dedham villagers marched to Pond’s home and confronted him. They were upset he had signed a letter to the Massachusetts governor, which they believed supported recent British actions against the Colonists. In the recounting this incident, Dedhamites, told how Pond and his servant, Jack, held the mob off by pointing a musket out the second floor window, thus giving the name of Pond’s servant for life. How long Pond owned Jack is unclear, but in the 1790 census, Pond lists one “all others” in the home. Pond handled his father’s estate in 1749. Although, his father had a sizable estate, he did not have an enslaved person listed in his inventory, indicating Pond did not inherit an enslaved person.

Dr. William Avery, earliest recorded doctor in town. Died 18 Mar 1686 Boston @ 65 yrs. He arrived from England in 1650 with his wife, Margaret (Albright) Avery and their three children, William, Mary and Robert. He and his family settled in Dedham by 1651. After they arrived they added Jonathan 1653, Rachel 1656, Hannah 1659 and Ebenezer 1662 to their family. William Avery not only practiced medicine, but he was also granted the right to operate a blacksmith shop. He also served as a town selectman for eight terms and represented Dedham in the Great and General Court of Massachusetts. After his wife died, William moved to Boston, where it is said he operated a bookstore. By the time he died in 1686 he had amassed sizable estate. In his will he mentions children William, Mary, Robert and Jonathan, and son-in-laws William Sumner (Rachel’s husband) and Benjamin Dyer (Hannah’s husband). It does not appear he had any enslaved people, none appear in town records and he does not list any in his will. The wills of his son William (died 1707) and Robert (died 1722) do not mention any enslaved people, but when his son Jonathan died in 1691, he had “A Negro Maide” valued at £9 listed in his inventory. Other Averys who enslaved people are:

- Grandson, John Avery (1686-1754), son of Robert, in his will left 2 enslaved people; Jack and Hope. His will was to let them choose which of his children they wanted to live with, and that they should never be sold.

- Granddaughter, Abigail (1699-1794), daughter of Robert, married John Richards. They were slaveholders. It appears they lived in the Third Parish, now Westwood, as they are buried in the old cemetery there.

- Grandson, William (1716-1796), son of William, had Titus, his “negro servant” baptized, 9 Jan 1757. William Avery & Sons are mentioned in the 1771 tax valuation as having 1 “servant for life.”

- Granddaughter, Sybil (b 1720), daughter of William married Ebenezer Pond. In the 1771 tax valuation Pond had 1 “servant for life.”

Peter Luce was born 1686 and he died 9 Nov 1753 in Dedham (at 67 years). It is not known where Luce was born. The Hatch genealogy says he was a Huguenot. In July of 1722 he married Elizabeth Hatch (1693-1735), she was the daughter of Nathaniel Hatch and Elizabeth Estes. The births of only three of their children are recorded in Boston vital records. When Luce died, he left a will and named five more children. The first three were not mentioned, most likely because they died young. Hatch genealogy also mentions Luce may had been married before he married Elizabeth Hatch, possibly making some of the five other children from a previous marriage.

Luce was a successful merchant who appears to have imported and exported goods, newspaper articles and advertisements indicate his business was quite large. In the 1720s And 1730s, he ran advertisements in local newspapers for the sale of many items, including: the sale of a sloops, Swede’s iron and sundry other tools, choice good cocoa, good Lisbon salt, Bristol beer, and even a “Negro Boy, about 18 years of age.” Luce operated out of a warehouse located on the docks in Boston. He owned homes on Newbury Street in Boston, and had a large estate in Dedham. He needed the labor of enslaved people to work his business as well as toil in his private homes.

In the summer of 1734, Luce’s enslaved man, London raped a woman, and ran away. Luce advertised a reward for his return, so that he could be brought to justice. Caught by September, London confessed to the crime and was put to death in November. In 1745, Luce’s “Negro fellow, Bridgewater” ran away taking a Luce’s horse with him. Bridgewater eventually returned to Dedham. He is most likely the “Ben. Bridg,” Peter Luce’s “negro servant,” that married an Indigenous woman named Sarah Waterman on 27 Apr 1752 at the Dedham church. Luce died in 1753, and in his will the inventory lists four “negro servants” by name: Bridgewater (£15), Topsham (£20), Jack (£25) and Ceasar (£20). In 1758, Luce’s executor advertised the sale of his 260 acre “commodious” estate in Dedham, which came with three valuable Negros. Dr. John Sprague bought the property.

Dr. John Sprague was born 1718 in Cambridge, son of Joseph Sprague and Sarah Stedman. He graduated from Harvard in 1737, and he continued his medical studies with Dr. Louis Delhonde of Boston. He married in 1745 to Elizabeth Delhonde (1725ish-1757), daughter of Dr. Delhonde. Soon after their marriage they bought a house on Winter Street in Boston, which came with two negro servants. John and Elizabeth had three sons. After the death of his wife, Sprague bought the Luce estate in Dedham, which “included three valuable negros.” He also bought the neighboring estate of Jonathan Fisher, and began practicing medicine in Dedham. In 1775, Sprague married Esther (Shourds) Harrison (1728-1811), the widow of a wealthy merchant, Charles Harrison ( -1766). The couple did not have any children, thus Esther inherited the bulk of Harrison’s estate. With the marriage of Sprague to the widow Harrison, their combined estate of this couple was enormous, they had land in Dedham, Canton, Dorchester, Milton, Stoughton, Randolph, Cambridge and Boston, assessed value in 1797 almost $72,000. During the Revolutionary war years, Dr. Sprague’s servant, Cuff Sprague served several times in the militia, for Jonathan Metcalf, who paid £66 to Sprague to have Cuff serve for him. Sprague died in 1797, his estate was administered, because Sprague did not leave a will. There do not appear to be any enslaved people counted in the extensive inventory, however, in 1790 he had four “all others” living at his Dedham property and in 1800 the Widow Sprague had one “all others” living with her.

In Dedham village, by the mid-1700s, had many wealthy landowners who were also enslavers. From studying their probate records, and cross referencing them with town vital records and family genealogies, most of these wealthy farmers are the direct descendants of the original settlers of Dedham. When the original settlers left an established town like Boston or Watertown for the unsettled forests of what would become Dedham, they received from the Great and General Court of Massachusetts, large tracts of land as an incentive to move. This grant included a smaller house lot in what would become the village area and a large parcel of land outside the village for farming. Clearing the land and building structures to live in and protect farm animals would have been one of the first projects these settlers had to tackle, but it would have been necessary to have a lot of help to accomplish such a project. Before the African slave trade gained a foothold in the American Colonies, the practice of employing indentured servants was used. Indentured servants signed a contract agreeing to work for a set amount of years, usually four to seven years to a master who owned the contract. During this time of indenture was given room and board in exchange for their labor. At the end of this contract, very often these servants received land, tools and a new suit of clothes, which was to help them establish a new life in the colonies. In Dedham, the names of some these indentured servants can be found on a Freeman’s list. (not all the names on this list were men who had been indentured servants). Once a man was deemed a freeman, he could own land, join the church and participate in town meetings. The 1681 census taken in Dedham to count the number of servants in town, illustrates that many Dedham families needed and utilized several forms of servitude on their farms. Looking at the change in servant demographics shows a growing use and acceptance of enslaved people in Dedham. Therefore it is not surprising to see that the families of Dedham’s original land grantees, who had large tracts of land, which often had small business on them, were the wealthiest people in town, and therefore were slaveholders.