Sambo Freeman died in 1797 a notation was made in town record that he was “nearly 80,” giving the year of his birth about 1719. No documentation has been found regarding Sambo’s early life. We do not know who his parents were or where he was born. He was owned by William and Bethiah Burgess of Medway. The bulk of their property came from Bethiah’s father, Josiah Rockwood (1654-1727), who left a will and had is estate inventoried but did not have an enslaved person. It is entirely possible, Sambo came into the Burgess family after 1727. The first time he appears in records is when his master, William Burgess brought him to the church in Medway to be baptized on September 16, 1739. Although there is no clue to the age of Sambo in church documents, it can be assumed he was old enough to made the decision to be baptized, giving further credence to his 1719 birth year. During his time with Burgess, or possibly before, Sambo learned carpentry skills, going on to be considered a master carpenter — a trade that served him well.

When the new year of 1754 dawned, Sambo’s life dramatically changed. In January, William Burgess died. He had quite a sizeable estate, which he left in totality to his wife, Bethiah. It appears that soon after Burgess’ estate was officially settled, Bethiah sold Sambo to John Adams of Wrentham, and then on April 6, 1754 Sambo bought his freedom from John Adams for £13 6s 8p. He took the surname “Freeman,” perhaps as a declaration of his free status. Published histories note Sambo moved to Holliston, but records from Medway show he enlisted in the town militia sometime around 1758 (his name appears in the records without a timeframe) and served in Capt. Adams Company during the French and Indian War. He was still living in Medway in 1762, when he was warned out of town. This is interesting, as Sambo was single having no family to support and able to work as a carpenter, so he should not have been viewed as a threat of becoming a town charge.

He was in Holliston, a neighboring town to Medway, by September of 1766 when he filed his intention to marry Eleanor “Nellie” Donahue, the widow of Cuff Oxford of Framingham. Eleanor brought four children to the marriage, and together Sambo and Eleanor had five children (Amos, Obediah, Nellie, Philip and Esther) between the years 1767 and 1777. It appears that Sambo did not serve in the military during the Revolutionary War, as his name does not appear on any muster rolls or in the book naming Soldiers and Sailors from Massachusetts.

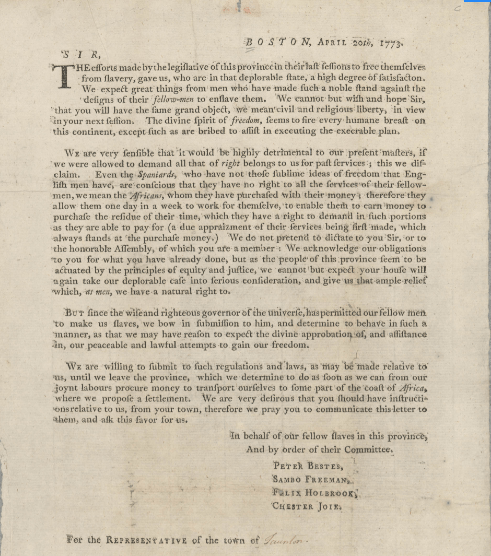

It is believed that this Sambo Freeman along with three other enslaved men, signed a letter to the governor of Massachusetts in April of 1773 asking that liberty be given to Massachusetts slaves. They further note that Spaniards allow their enslaved one-day-a-week to work for themselves in order to earn money to buy their freedom. Once they are freed, they state their plan was to work to save money to buy passage to Africa for resettlement. What is confusing about this letter in regards to Sambo, is it infers the four men who signed it were at that time, enslaved and were residents of Boston. Sambo Freemen was living in Holliston, a free man, and had bought his freedom almost twenty years earlier, and judging by his estate, Sambo could have easily afforded passage to Africa for his entire family and still had money left over. The signatories on this April letter were Peter Bestes, Felix Holbrook, and Chester Joie, as well as by Sambo Freeman. This letter was a follow up to a similar letter written by an enslaved man simply named “Felix,” who was probably Felix Holbrook on the second letter. It should be noted that further research regarding Felix and Chester have not yielded any other information about these men, which admittedly is not unusual for enslaved people in the 1700s in Massachusetts, but it is conceivably possible some sort of vital record would exist on at least one of these men. Peter Bestes published an advertisement in a Boston Newspapers asking to buy his freedom. The other odd factor about this letter was written for the “Representative of the town of Thompson,” and there is no such town in Massachusetts. These inconsistencies the April letter make it questionable that the Sambo Freeman who signed this letter, is not the Sambo Freeman who was living in Holliston. However, it should be noted that the result of these letters, plus two more subsequent letters, was the Massachusetts State Legislature voted to prohibit slave trade from Africa, but did not end slavery in the state.

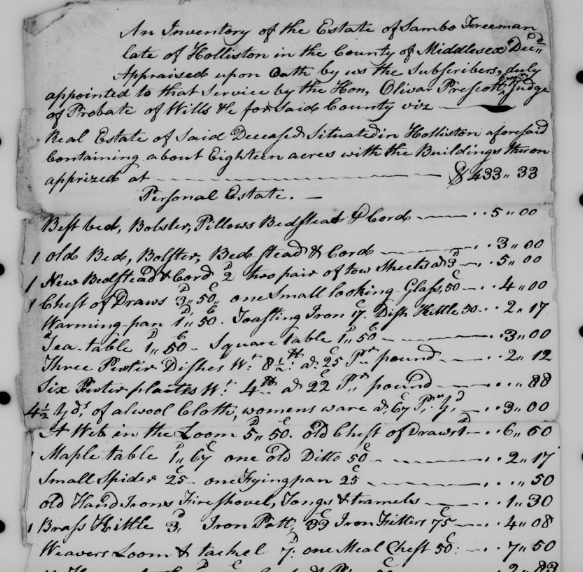

On September 30,1797, Sambo died of a fever at nearly 80 years old. Holliston minister, Rev. Timothy Dickinson, noted in his diary he had been a few times to visit Sambo when he was ill, he also recorded is death in his diary as well as a notation on October 2, that the “Negros have, today, paid great respect to Sambo’s character. They buried him with great decency.” The following year, on September 16, Eleanor (Donahue) Freeman died, and a month later on October 16th their youngest child Esther died. Holliston vital records note they died of “a fever.” Sambo had experienced a lot of success as a free man. He was a skilled laborer and was therefore able to find steady employment. When he died, he left a sizable estate to his four surviving children in a will he wrote they day before he died. He owned 18 acres of land with “with the buildings there on,” which was valued at $433.33. This property is also noted in the Holliston tax schedule of 1798. Sambo’s personal estate was valued at $522.59. What is interesting to note is two years later, Sambo’s son Obed died in the poor house. It raises the question of what happened to his share of his parent’s estate, and why was he not able to support himself, because as a lad, it would make sense he would have helped his father with carpentry jobs.

Listed in the inventory of Sambo’s estate was a weaving loom, with web in the loom and several yards of cloth. This may indicate that Eleanor was a weaver, and her skill would have contributed greatly to the family’s income. It appears, both Sambo and Eleanor were able to find jobs as skilled laborers, which would have contributed to their financial success. Highlighting the notion that people of color, who skilled laborers, appear to have had an easier time supporting themselves.