In the towns that were set off from the original Dedham land grant, the slave population was small, a little over one percent (1.291%) of the over all population. They were largely agricultural communities, which had been initially established around a mill; in the 1600s and into the mid-1700s, the majority of these mills were small operations, either sawmills or gristmills, and the farms in these towns were subsistence farms owned by individual families. These mills and farms did not need slave labor to run them. Which suggests the question: Who were the main slave owners in these small towns and what did they need them for?

Records tell us who these slave owners were, and it is extremely interesting to note that slaveholders were often the town’s ministers; at least those who were ministering in the mid-1700s. Early ministers, those who ministered between the 1600s to early 1700s in Dedham grant towns, do not seem to have been slave owners, at least no documentary evidence has yet been found. In church records, ministers or the mid-1700 record the marriage or death of a “negro,” often noting to whom that person belonged, and frequently that person was the minister himself. Although not all ministers recorded vital records for all enslaved people, many left wills because they were quite wealthy, and in their wills they dispersed (or freed) their “negro servants.” Only two towns, Wrentham and Dover, do not seem to have records indicating their ministers were slave owners (or records have yet to be found). Wrentham, one of the oldest settled towns, does not show slave owner ship in published vital records, and wills of their earliest ministers do not mention enslaved people. The Dover church was established in the mid-1700s, so it is possible their minister was a slave owner, but like Wrentham, the published Dover vital records do not mention enslaved people. In addition, their minister died after slavery was legally ended in Massachusetts, so he could not legally had slaves to leave behind.

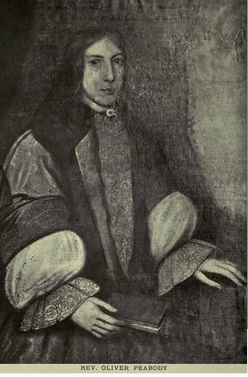

Rev. Oliver Peabody, the second minister of Natick, left a will when he died in 1752. In it he left two slaves; Rose and Prince. In his will, he gives his “negro servant,” Rose to his wife, noting that upon his wife’s death, Rose may be freed. He also mentions his “negro man servant,” Prince, who he wishes to be freed a year after Rev. Peabody’s death. What is extraordinary about this situation is that Natick’s first minister, Rev. John Elliot, the 1651 founder of Natick, and whose mission was to Christianize indigenous people – the very same people the white settlers had been enslaving. Natick was (and is) known as the “Praying Indians” town, because Elliot established a church and a community for the native Christian population. Natick’s vital records published in the early 1900s, a project sponsored by historical organizations and assembled by local committees, did not single out baptisms, marriages or deaths of black or native people, instead they are listed alphabetically with all white people. Most of these vital record books that included information, added it to the end of each section, after “Z.” Natick’s format reflects how they felt about their native peoples; that they were part of and not separate from its white population. Regarding slavery, John Elliot noted that he “lamented . . . with a bleeding and burning passion, that the English used their Negroes but as their Horses or the Oxen, and that so little care was taken about their immortal Souls.” Natick histories tell of how Rev. Elliot built his flock and how Rev. Peabody, followed by Rev. Stephen Badger continued to minister to the indigenous people of Natick, many of whom had intermarried with local black populations. So it is fascinating to find that Rev. Peabody was a slave owner.

Why ministers need enslaved people is a lot less clear. Town histories or church records do not indicate when or why any of the ministers of the original Dedham land grant became slave owners. It is highly likely these ministers needed help to maintain their homes and farms, as tending to their ministerial duties would have made it difficult to stay on top of daily chores. The minister, like his flock, would have had a small farm complete with livestock to tend. Very often ministerial duties would require them to visit other churches for installation ceremonies or to consult with neighboring congregations on difficult issues. Frequently, a minister had pupils to prepare for college, because they were often the most educated person in town. Then there were the tasks all ministers performed; visiting the sick and dying, attending church meetings, and writing and delivering a weekly sermon. It should be noted that Sunday services were all day affairs. The congregation would break for lunch, then go back to church for the afternoon. Ministers were well paid by their congregation and students, often making them the wealthiest person in town, so the cost of owning an enslaved person was not a financial difficulty, and most likely a need extra pair of hands.

Today, many of the First churches established in the original Dedham land grant towns are struggling with this uncomfortable history. Having a clear understanding of how and why their early ministers owned slaves, as well as understanding how these enslaved people were treated, would be welcome information to know. However, the fact is most enslaved people left little to nothing behind to help educate today’s congregations. Their voices are silent.