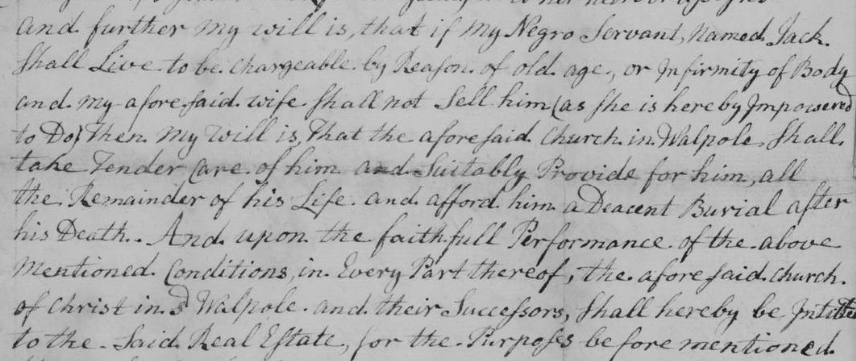

Very little is known about Jack Robbins before he came to Walpole, this is due to the fact that no documentation has been found to date, regarding Jack until after he becomes a ward of the Walpole church. We know in the 1754 Massachusetts Slave census only counts one female slave in town under the age of sixteen. The first time Jack appears in any records is in Deacon Ezekiel Robbins will that he wrote in 1766 and was probated in 1772. It is assumed that Jack arrived in Walpole sometime between 1755 and 1760. We do not know when he was born and where he was from, or who his parents were. He was most likely born into slavery sometime in the 1730s. He was enslaved by Deacon Ezekiel Robbins (1695-1772) and his wife Mary (Clap) Robbins (1705-1783), an aging childless couple who most likely needed assistance running their large farm and tavern. In the Deacon’s will he left his entire estate to his wife, but upon her death, he wanted the church to have his real estate, but on the condition they maintain (1) an orthodox minister, (2) pay a legacy to his great niece and nephew, and (3) to take “tender care” of Jack should he live to be chargeable and to afford him a decent burial. In February of 1783, the widow Robbins died and the church voted to accept the terms of Deacon Robbins gift. It should be noted that a few months later, in July, Massachusetts Judge William Cushing issued his directive to a jury stating that “slavery is in my judgment as effectively abolished as it can be by the granting of rights and privileges wholly incompatible and repugnant to its existence,” and that “perpetual servitude can no longer be tolerated in our government.”

In 1787, Jack was “of Attleborough” when he married Hannah Eaton, a free person of color from Norton. Hannah was of mixed heritage; she was part African and part Wampanoag. It is not known when Jack went to Attleborough or for how long he lived there, as there are no documents that contain information regarding Jack during this time frame. Jack and Hannah appear to have returned to Walpole around 1789 when the church formed a committee to oversee Jack’s care. In the 1790 US Federal Census, records two “all other people” living in the home of Peter Morse. It is highly likely this is Jack and Hannah. In February of 1791, the church decided to look into the legality of Jack and Hannah’s marriage, which would have been confirmed by the Attleboro town clerk, as they were indeed legally married. Checking on the legality of their marriage seems to be regarding weather the church wondered if they were also responsible to care for Hannah or not. They seem to have received acknowledgment of the marriage, because on May 28, 1792, they voted that in accordance with Deacon Robbins’ will, their “obligation (was) to care and provide for Jack… personally and individually…& no other wife.” A year later on April 8, 1793, the church called a meeting, where first they confirmed that they were “satisfied with ye management of sd committee since May 28, 1792 in ye affairs relative to Jack instructed to ye care.” The very next thing they did at that meeting was to select three representatives from the church to go to the Court of Common Pleas as Jack filed a case of some sort against the Church. It is unclear what this case was about, but because the two successive actions the church voted on April 8th, seem to indicate that the case had to do with Jack and Hannah being together. There is no record of the case on file in the Massachusetts Judicial Archives, which may indicate a settlement was agreed upon before they went to court. But if the 1800 US Federal census is any indication, only two “all other people” are recorded in Walpole living in separate homes.

Jack’s wife, Hannah Eason was born free around 1750 in the Norton Massachusetts area, probably on the Titticut reservation, as her father purchased 90 acres there in 1748, from his father-in-law. It should be further noted, that Native communities did not keep vital records, as that was not part of their traditions, which makes it difficult to know Hannah’s birthdate. She was the daughter of Caesar Eason and Mercy Gonduary. Her parents married 20 Sept 1736 in Little Compton, RI. Both her parents were of mixed ethnicities – Native American and African, and both were born free. It is not unusual to find that many of New England’s Native people intermarried with people of African heritage – both enslaved and freed. During the 1600s, many of New England’s native population, mostly male, were captured and shipped away, often to Caribbean plantations, where they were enslaved. Around the start of the eighteenth century, most of New England’s enslaved population, were African males. As these men were freed or escaped, they found a safe and familiar haven in Native communities. It is from this history and the Eason and Gonduary families connection to Titticut land, we can draw the conclusion that Hannah’s family was both of African and Native American ethnicities.

Hannah first appears in documents when she marries, and then she is mentioned several times in Walpole town and church records. It should be mentioned, that in Hannah’s generation her siblings sometimes used “Caesar” as their surname, and sometimes they used “Eason.” Hannah was married twice, first to Francis Sisco in 1780 and then to Jack Robbins, and both times she used “Eason” to register the marriages, and once in Walpole, she was known as “Hannah Jack.” Hannah’s life in Walpole was fraught with trouble. It stared in 1791, as it seems the church did not want to pay to support Hannah. That is the year the church decided to look into the legality of Jack and Hannah’s marriage, which was indeed legal, so a year later they voted that the will of Deacon Robbins was to care for Jack and “no other wife.” Walpole records indicate that in 1807, Samuel Guild was paid $21.83 for “keeping Hannah a black woman,” and at that time, the town also decided to “make an inquiry whither Hannah belongs to the town to maintain or not.” By the town, deciding to the look into Hannah’s origins, was about the town trying to figure out if she should be Walpole or Norton’s responsibility to support. Up until the early 1900s, it was the responsibility of towns to support their poor, and towns often “warned out” indigent people who might become a financial problem for a town. In 1808, the town “voted to have the Selectman carry Hannah Jack to jail at Dedham, if she behave well in their opinion they may neglect to carry her to Dedham jail.” It is not known what Hannah may or may not have done that upset the selectman, or even if she was jailed or not, but it certainly appears to be an intimidation technique.

During the months of June and July in 1795, the Church ran advertisements in Boston newspapers stating they, “in accordance with Dea. Robbins will, take suitable care” of Jack and therefore not responsible all debts Jack may incur. It is not known why Jack had gone to Boston he would not have needed a job, as the church was supporting him, perhaps this was part of an on-going disagreement regarding Hannah. In December 1810 the Church records in its financial book that $160.33 was spent for two years (1809 & 1810) support of Jack and for his funeral expenses. A secondary source says he died at the old Turner place on Elm Street, which make sense as in 1810 the town paid Nathan Turner for the support of Hannah. It does not appear Jack and Hannah had any children, as none are mentioned in any town or church records. It is not known when Hannah died. Her death is not noted in Walpole vital records, there is no published obituary, and a gravestone was not erected in a local cemetery. If she was not mentioned a handful of times in town records, (and often not in positive terms), her entire long life would have gone unnoticed.

The pieces of documentation that exist on Jack and Hannah, indeed help to flesh out their lives. They lived on the fringe of Walpole society, most likely in poverty, and it seems they were not treated well. The Walpole church was charged with taking “tender care” of Jack, if they wanted to inherit a sizable piece of real estate. It is clear they met all his physical needs. He always had a roof over his head, food in his belly, and clothes on his back, but all those choices were made for him. Especially when it came to his wish to live with his wife Hannah. Jack may have been free according the Massachusetts Constitution, but it seems clear, that he was never free to make his own decisions.