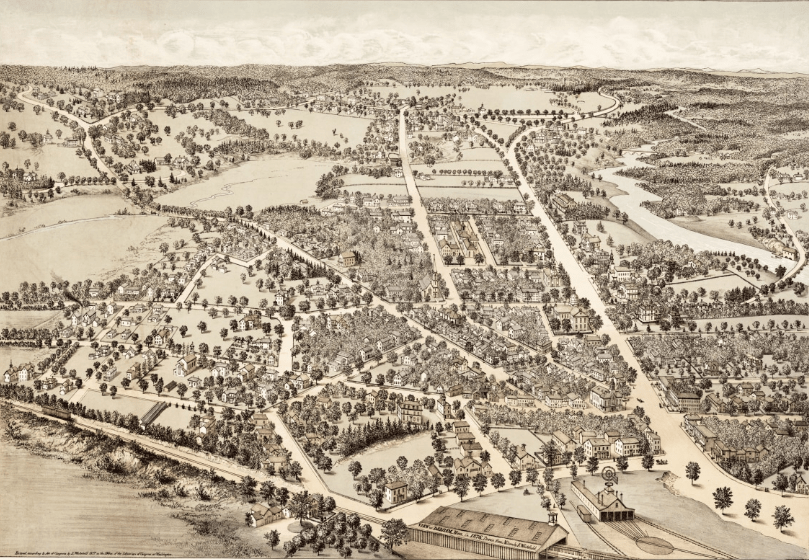

Dedham was the largest town of all the original Dedham land grant towns; both physically and in population. It was on the Boston–Providence Highway, making it an important stop between the two cities, and several wealthy Boston merchants maintained estates there. From reading the wills of several of Dedham’s wealthiest residents and by looking at published church records, a list of approximately fifty enslaved people can be created. When an internet search is taken for “slavery in Dedham,” articles come up about a man who lived in the town, who had escaped from slavery in the south just before the Civil War, and nothing about their own early residents who were enslavers or the people that were enslaved there. So it is curious that Dedham does not have any of this history easily accessible. It appears to be a truly hidden history.

Presumably, some enslaved people who lived and worked in Dedham would have been skilled laborers, due to the fact that many local enslavers were blacksmiths, millers and tavern keepers. Plus, it is possible there were other kinds of skilled enslaved people in Dedham, who may have been trained as tailors, bakers, carpenters, shoemakers, etc. who have yet to be discovered. When slavery gradually ended starting in 1783, records show many people who had been enslaved in many of the original Dedham land grant communities, remained in or near their communities. Knowing there would be a need for labor, and add the notion that some may remain in a familiar community, it would seem a few formerly enslaved people could be found living in Dedham as a free person, especially as there would always be a demand for both skilled and manual labor. Yet, it is difficult to locate Dedham residents who had been formerly enslaved there.

This study has identified many enslaved people who lived in Dedham by their first names. In many cases, what surnames they took or if they took a new first name, when they became free, is unknown. Making it difficult to track them through scant records. For instance Caesar Hunt of Medway bought his freedom, he took the name “Peter Warren.” His name change is noted in his emancipation papers. Without this documentary evidence, finding out what happened to Caesar Hunt would have been impossible. In Dedham there were three enslaved named Caesar living in town. It appears the Caesar who was part of Peter Luce’s estate in 1753 was one of the “valuable Negros” sold with the estate to Dr. John Sprague. In May 1800, Caesar “Negro of Mrs. Sprague” died. However, it possibly appears these may be two separate Caesars; the one who died in 1800 was reported to be 54 years old, making 1745/6 his birth year, which may or may not make him too young to be a “valuable Negro” in 1753. Or maybe he was Capt. James Fales’ Caesar, who was baptized in 1765? Also in Dedham’s records is Cato, an enslaved man of Nathaniel Ames. He first appears in records 1745, when he and his master are attacked by Ames’ brother-in-laws and then in 1764 he is listed in Ames’ inventory. In May of 1794, Dinah, wife of Cato Freeborn died and four year’s later Cato’s daughter (unnamed) died. Cato remarried in 1796 to Eleanor Savage and in 1798 he is “of Boston” when his name appears on a letter confirming his membership to Prince Hall’s Grand Lodge (Masons). Is Ames’ Cato the same as Cato Freeborn? And what about Frank, the man who had been previously enslaved by Richard Woodward? When he died in 1793 he was 70 years old, making his year of birth 1723. Was he someone Richard Woodward inherited from his first father-in-law, Peter Luce? Or maybe he was part of Nathaniel Ames’ estate that he would have taken possession of when he married Ames’ widow. If that’s the case Frank could be any one of six enslaved men owned and inventoried in either Luce’s or Ames’ estates. It is tricky to identify and follow these formerly enslaved men though time as records regarding them are hard to find.

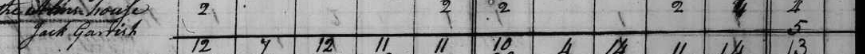

Census records can be helpful in locating and tracing the lives of people of color…or as they are recorded in the censuses “all other people.” In the 1790 census, there is not one “all other people” who is listed as the head of their own household in Dedham. All sixteen “all other people,” counted in this census are living in someone’s home. However, by the 1800 census, there is one family of color in Dedham that has established their own home – The family of Jack Garish (1744-1817).

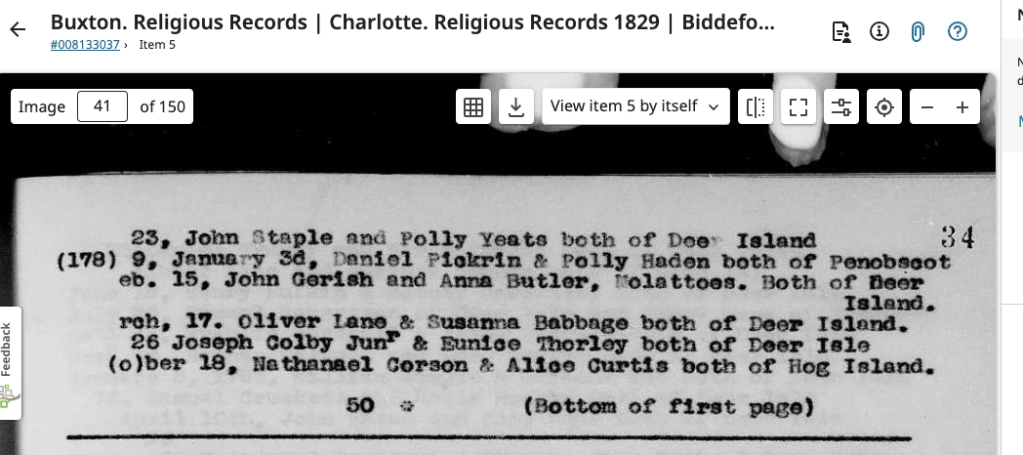

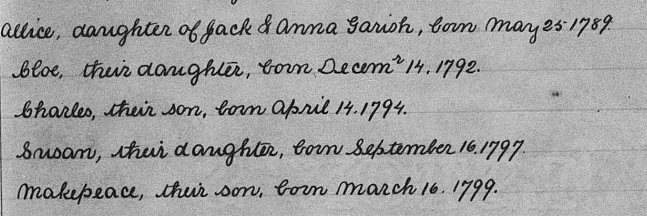

Jack was likely enslaved in Dedham most of his life, he could be one of three possible Jacks who appear in estate inventories between 1753 and 1764. The births of his children are recorded in Dedham vital records, as is his death. For some unknown reason, Jack settled briefly in Hancock County Maine. His marriage on February 15, 1787 to Anna Butler is recorded in Deer Isle records, and he is recorded in the 1790 census living in Conduskeag Plantation, Maine (today the greater Bangor area). He reports 3 “all others” living in the home, however, the census taker notes this is “Jack Garrish, a Mulatto, his wife & child.” We do not know who Jack’s parents were, nor to we know anything about his wife Anna “Nancy” Butler. Jack and Anna likely returned to Dedham in the early 1790s, and became the parents of five children: Elcy/Alice 1788, Cloe in 1792, Charles in 1794, Susan in 1797 and Makepeace in 1799. Makepeace died in young.

It appears Jack and Anna spent the majority of their married life in Dedham. They were never warned out of town, indicating they “belonged” to Dedham. Warning outs happened frequently if someone moved into a new town and was thought to be poor. Town leaders would “warn out” poor people (send them back to their home community) which would prevent them from becoming a charge on the town. In the case of Ishmael Coffee (1741-1823ish), a free person of color who had lived in Medway, who as an old man, he became a charge on the town of Medway. Medway sued the town of Needham for his support. Ishmael was born in Needham and Medway’s argument was that he belonged to Needham. Needham’s argument was that because Ishmael had lived in Medway for over fifty years, he belonged to Medway. Needham lost the case and had to help support Ishmael and his wife.

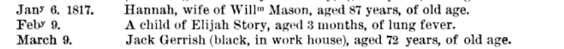

When Jack died the town noted that he had been living in the workhouse. Because Jack does not appear in any other censuses as a head of household, except for the 1790 and 1800, nor does he appear on any tax list as a renter or as a landowner, it is highly likely he found unskilled labor jobs. Ending up in the workhouse, and not owning any assets, would seem to indicate Jack struggled financially. Some fifteen years later, in 1832, Anna remarried to Caesar Nichols (1759-1843). Caesar was born into slavery in Poughkeepsie, New York, he served in the Revolutionary War, and arrived in Dedham in 1802 carrying a reference letter speaking to his outstanding character. He had been previously married, but did not have any children. He appears in several of the US Federal censuses living in Dedham. In the 1840 census, Caesar Nichols is listed living by himself, giving the appearance that Anna died in the 1830s. Anna’s death is not recorded in town records, further illustrating how people of color are marginalized

Although, they seem to have grown up poor, Jack and Anna’s children appear to have been more financially secure as adults. Elcy and Charles stayed in Dedham. Elcy lived to be 70 years old. She never married. When she died she left a will, giving her entire estate to the Mason Richards family. Elcy had almost $2000 worth of assets, her sister Susan, and her nieces and nephews contested the will. Charles married to Hannah Lewis and they had two daughters who grew to adulthood. Charles died in 1845 at 50 years old. Daughter Cloe married Philip Ames (1791-1858) and together they settled in Windsor, Vermont. Census records show they had about ten children, but only the names of four can be found. Cloe’s death date has not been found, but she appears to have died around 1845. Daughter Susan married Jeremiah Slocum (1788-1880ish), they settled in North Providence, Rhode Island and were the parents of nine children. Susan died in 1867.

Jack and Anna Garish, just like Cato and Dinah Freeborn, Caesar (Sprague), Frank (Woodward) (all of Dedham) and Ishmael Coffee (of Medway), all lived on the edges of white society. Most likely finding jobs as unskilled laborers and struggling to support themselves and their families. This lack of evidence illustrates how little they all had and how little white society cared about them. Making their stories, just like so many in similar situations, truly the hidden history of the lives of the enslaved and the lives of the formerly enslaved.