In 1620 the Pilgrims established Plymouth Colony and ten years later, the Puritans established the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Not long after these settlements were formed, the colonists began enslaving New England’s indigenous people; many native people were captured during the Pequot War (1636-1638), some were transported to the West Indies and others were forced into labor locally. In February of 1638, Governor John Winthrop recorded what is believed to be the arrival of the first Africans in Boston. He noted that the ship Desire had landed in Boston carrying a shipment of “some cotton, tobacco and negros” from Barbados. In 1641, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was the first colony to adopt a law supporting slavery. Under section 91 of the “Body of Liberties” states:

“There shall never by any bond slavery, villeinage, or captivity amongst us unless it be lawful captives taken in just wars, and such strangers as willingly sell themselves or are sold to us. And these shall have all the liberties and Christian usages which the law of God established in Israel concerning such persons cloth morally require. This exempts none from servitude who shall be judged thereto by authority.”

In 1643, New England colonies adopted the fugitive slave law, which provided for the return of a fugitive slave back to the colony from which the slave had fled. In 1670, the Bodies of Liberties was amended to include the offspring of enslaved women, these children would also be considered slaves. The Bodies of Liberties eventually became an article within The Articles of New England Confederation, thus legalizing slavery throughout New England.

By the mid-1600s, slave labor was needed in New England, as the distilling of rum had become a major industry. New Englanders needed sugar to make rum, which was then shipped to British colonies in other parts of the world; those ships returned with a cargo of African men, women and children destined for the sugar plantations in the Caribbean. Once off loaded their African cargo, these ships then took on a new cargo of sugar to deliver to New England. Historians call this shipping sequence the “Triangular Trade.” Slave labor was needed work at these busy ports, for loading and unloading ships, as well as for the shipbuilding and rum making industries. It is because of these industries demand for labor that the highest population of enslaved people in New England either lived in well-populated towns or in coastal villages.

By the early 1700s, a variety laws were passed to restrict the movements of people of color. For instance, they could not be out after dark, and interracial marriages were deemed illegal. Other laws were created to protect the cities and towns from indigent people of color. In 1703 a law required a slave owner who wanted to emancipate one of his slaves, (usually because the slave was too infirm to work and the owner did not want to take care of them) to post a bond to the town, which would support the emancipated person should they end up on the town’s poor rolls.

Between 1760 and about 1775, several freedom cases were brought to Massachusetts courts, where enslaved people sued their owners for their freedom. These cases had mixed results. In 1780, after the Revolutionary War, three freedom cases changed how Massachusetts legally viewed slavery. These cases sued for freedom using the recently written and ratified Commonwealth of Massachusetts Constitution, which included a Declaration of Rights that stated:

“All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights: among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.”

Although these cases dragged through Massachusetts state courts for several years, often with mixed results, eventually one came before the Massachusetts State Supreme Court for a decision. On July 8, 1783, Massachusetts Supreme Court Chief Justice Cushing, a slave owner himself, in the case the Commonwealth v Jennison, referred to as one of the “Quock Walker Cases,” found that “slavery is in my judgment as effectively abolished as it can be by the granting of rights and privileges [in the constitution] wholly incompatible and repugnant to its existence,” insinuating that enslaved people living in Massachusetts were considered free per the state constitution. It appears Cushing was telling the jury this case was not about Walker being a slave, because it had been decided in other cases, he was free, but it was about Jennison (Walker previous enslaver) assaulting Walker. The jury found in favor of the Commonwealth finding Jennison guilty of the assault. This case became the turning point for slavery in Massachusetts, and is often pointed to as the ending of slavery in the state, although it should be noted, it was by means of judicial interpretation and not through a legislative action. Cushing’s directions are seen as a statement that meant all enslaved people living in Massachusetts were considered free, plus the judicial decisions that “freed” Brom, Bett (Brom, Mum Bett v Ashley) and Walker were based on the Massachusetts Constitution. An official law or amendment was never written specifically outlawing slavery in Massachusetts, probably because the Commonwealth’s constitution was law. However, this does not mean that enslaved people in Massachusetts were immediately emancipated; many unscrupulous owners withheld this information from their enslaved people, hoping to get as much free labor as possible before they heard the news for themselves. Some owners quickly took their enslaved people to nearby states where slavery was legal to be sold before they knew they were free.

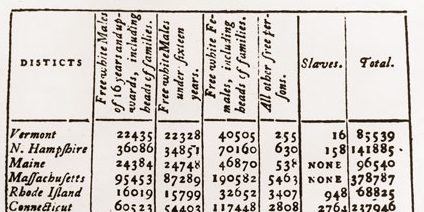

It should be noted that for Massachusetts, the 1790 Federal Census does not record any slaves in the state, some believe this proves all had been freed. However, George H. Morse in his 1866 book, Notes on Slavery in Massachusetts, notes a census taker for the 1790 census told his family that many people simply lied if they had slaves, telling the census taker they had no slaves, when in reality, the did, recording their slaves as “all other people.” Other official forms of documentation post 1783, such as town vital records and probate records do not record people of color as belong to someone, leaving such an entry unnoted. Thus, making it difficult for today’s historians to figure out whether a person of color was enslaved for free after 1783. However, today most historians agree slavery ended gradually in Massachusetts.